|

THE FOUNDATIONS OF INDIAN CULTURE

SRI AUROBINDO

Contents

|

|

Religion and Spirituality

I HAVE described the framework of the Indian idea from the outlook of an intellectual criticism, because that is the standpoint of the critics who affect to disparage its value. I have shown that Indian culture must be adjudged even from this alien outlook to have been the creation of a wide and noble spirit. Inspired in the heart of its being by a lofty principle, illumined with a striking and uplifting idea of individual man- hood and its powers and its possible perfection, aligned to a spacious plan of social architecture, it was enriched not only by a strong philosophic, intellectual and artistic creativeness but by a great and vivifying and fruitful life-power. But this by itself does not give an adequate account of its spirit or its greatness. One might describe Greek or Roman civilisation from this outlook and miss little that was of importance; but Indian civilisation was not only a great cultural system, but an immense religious effort of the human spirit. The whole root of difference between Indian and European culture springs from the spiritual aim of Indian civilization. It is the turn which this aim imposes on all the rich and luxuriant variety of its forms and rhythms that gives to it its unique character. For even what it has in common with other cultures gets from that turn a stamp of striking originality and solitary greatness. A spiritual aspiration was the governing force of this culture, its core of thought, its ruling passion: Not only did it make spirituality the highest aim of life, but it even tried, as far as that could be done in the past conditions of the human race, to turn the whole of life towards spirituality. But since religion is in the human mind the first native, if imperfect form of the spiritual impulse, the predominance of the spiritual idea, its endeavour to take hold of life, necessitated a casting of thought and action into the religious mould and a persistent filling of every circumstance of life with the religious sense; it demanded a pervading religio-philosophic culture. The highest spirituality Page-121 indeed moves in a free and wide air far above that lower stage of seeking which is governed by religious form and dogma; it does not easily bear their limitations and, even when it admits, it transcends them; it lives in an experience which to the formal religious mind is unintelligible. But man does not arrive immediately at that highest inner elevation and, if it were demanded from him at once, he would never arrive there. At first he needs lower supports and stages of ascent; he asks for some scaffolding of dogma, worship, image, sign, form, symbol, some indulgence and permission of mixed half-natural motive on which he can stand while he builds up in him the temple of the spirit. Only when the temple is completed can the supports be removed, the scaffolding disappear. The religious culture which now goes by the name of Hinduism not only fulfilled this purpose, but, unlike certain other credal religions, it knew its purpose. It gave itself no name, because it set itself no sectarian limits; it claimed no universal adhesion, asserted no sole infallible dogma, set up no single narrow path or gate of salvation; it was less a creed or cult than a continuously enlarging tradition of the Godward endeavourof the human spirit. An immense many-sided and many- staged provision for a spiritual self-building and self-finding, it had some right to speak of itself by the only name it knew, the eternal religion, sanätana dharma. It is only if we have a just and right appreciation of this sense and spirit of Indian religion that we can come to an understanding of the true sense and spirit of Indian culture. Now just here is the first baffling difficulty over which the European mind stumbles; for it finds itself unable to make out what Hindu religion is. Where, it asks, is its soul? Where is its mind and fixed thought? Where is the form of its body? How can there be a religion which has no rigid dogmas demanding belief on pain of eternal damnation, no theological postulates, even no fixed theology, no credo, distinguishing it from antagonistic or rival religions? How can there be a religion which has no papal head, no governing ecclesiastic body, no church, chapel or congregational system, no binding religious form of any kind obligatory on all its adherents, no one administration and discipline'? For the Hindu priests are mere ceremonial Page-122 officiants without any ecclesiastical authority or disciplinary powers and the Pundits are mere interpreters of the Shastra, not the law-givers of the religion or its rulers. How again can Hinduism be called a religion when it admits all beliefs, allowing even a kind of high-reaching atheism and agnosticism and permits all possible spiritual experiences, all kinds of religious adventures? The only thing fixed, rigid, positive, clear is the social law, and even that varies in different castes, regions, communities. The caste rules and not the Church; but even the caste cannot punish a man for his beliefs, ban heterodoxy or prevent his following a new revolutionary doctrine or a new spiritual leader. If it ex- communicates the Christian or the Muslim, it is not for religious belief or practice, but because they break with the social rule and order. It has been asserted in consequence that there is no such thing as a Hindu religion, but only a Hindu social system with a bundle of the most disparate religious beliefs and institutions. The precious dictum that Hinduism is a mass of folk- lore with an ineffective coat of metaphysical daubing is perhaps the final judgment of the superficial occidental mind on this matter. This misunderstanding springs from the total difference of outlook on religion that divides the Indian mind and the normal western intelligence. The difference is so great that it could only be bridged by a supple philosophical training or a wide spiritual culture; but the established forms of religion and the rigid methods of philosophical thought practised in the West make no provision and even allow no opportunity for either. To the Indian mind the least important part of religion is its dogma; the religious spirit matters, not the theological credo. On the contrary, to the western mind a fixed intellectual belief is the-most important part of a cult; it is its core of meaning, it is the thing that distinguishes it from others. For it is its formulated beliefs that make it either a true or a false religion, according as it agrees or does not agree with the credo of its critic. This notion, however foolish and shallow, is a necessary consequence of the western idea which falsely supposes that intellectual truth is the highest verity and, even, that there is no other. The Indian religious thinker knows that all the highest eternal verities are truths of the Page-123 spirit. The supreme truths are neither the rigid conc1~sions of logical reasoning nor the affirmations of credal statement, but fruits of the soul's inner experience. Intellectual truth is only one of the doors to the outer precincts of the temple; And since intellectual truth turned towards the Infinite must be in its very nature many-sided and not narrowly one, the most varying intellectual beliefs can be equally true because they mirror different facets of the Infinite. However separated by intellectual distance, they still form so many side-entrances which admit the mind to some faint ray from a supreme Light. There are no true and false religions, but rather all religions are true in their own way and degree. Each is one of the thousand paths to the One Eternal. Indian religion placed four necessities before human life. First, it imposed upon the mind a belief in a highest consciousness or state of existence universal-and transcendent of the universe, from which all comes, in which all lives and moves without knowing it and of which all must one day grow aware, returning to- wards that which is perfect, eternal and infinite. Next, it laid upon the individual life the need of self-preparation by development and experience till man is ready for an effort to grow consciously into the truth of this greater existence. Thirdly, it provided it with a well-founded, well-explored, many-branching and always enlarging way of knowledge and of spiritual or religious discipline. Lastly, for those not yet ready for these higher steps it provided an organisation of the individual and collective life, a framework of personal and social discipline and conduct, of mental and moral and vital development by which they could move each in his own limits and according to his own nature in such a way as to become eventually ready for the greater existence. The first three of these elements are the most essential to any religion, but Hinduism has always attached to the last also a great importance; it has left out no part of life as a thing secular and foreign to the religious and spiritual life. Still the Indian religious tradition is not merely the form of a religio social system, as the ignorant critic vainly imagines. However greatly that may count at the moment of a social departure, however stubbornly the conservative religious mind may oppose all pronounced or drastic change, still the core of Hinduism is a Page-124 spiritual, not social discipline. Actually we find religions like Sikhism counted in the Vedic family although they broke -down the old social tradition and invented a novel form, while the Jains and Buddhists were traditionally considered to be outside the religious fold although they observed Hindu social custom and intermarried with Hindus, because their spiritual system and teaching figured in its origin as a denial of the truth of the Veda and a departure from the continuity of the Vedic line. In all these four elements that constitute Hinduism there are major and minor differences between Hindus of various sects, schools, communities and races; but nevertheless there is also a general' unity of spirit, of fundamental type and form and of, spiritual temperament which creates in this vast fluidity an immense force of cohesion and a strong principle of oneness. The fundamental idea of all Indian religion is one common to the highest human thinking everywhere. The supreme truth of all that is is a Being or an existence beyond the mental and physical appearances we contact here. Beyond mind, life and body there is a Spirit and Self containing all that is finite and infinite, surpassing all that is relative, a supreme Absolute, originating and supporting all that is transient, a one Eternal. A one transcendent, universal, original and sempiternal Divinity or divine Essence, Consciousness, Force and Bliss is the fount and continent and inhabitant of things. Soul, nature, life are only a manifestation or partial phenomenon of this self-aware Eternity and this conscious Eternal. But this Truth of being was not seized by the Indian mind only as a philosophical speculation, a theological dogma, an abstraction contemplated by the intelligence. It was not an idea to be indulged by the thinker in his study, but otherwise void of practical bearing on life. It was not a mystic sublimation which could be ignored in the dealings of man with the world and Nature. It was a living spiritual Truth, an Entity, a Power, a Presence that could be sought by all according to their degree of capacity and seized in a thousand ways through life and beyond life. This Truth was to be lived and even to be made the governing idea of thought and life and action. This recognition and pursuit of something or someone Supreme behind all forms is the one universal credo of Indian religion, and if it has taken a Page-125 hundred shapes, it was precisely because it was so much alive. The Infinite alone justifies the existence of the finite and the finite by itself has no entirely separate value or independent existence. Life, if it is not an illusion, is a divine Play, a manifestation of the glory of the Infinite. Or it is a means by which the soul growing - in Nature through countless forms and many lives can approach, touch, feel and unite itself through love and knowledge and faith and adoration and a Godward will in works with this transcendent Being and this infinite Existence. This Self or this self- existent Being is the one supreme reality, and an things else are either only appearances or only true by dependence upon it. It follows that self-realisation and God-realisation are the great business of the living and thinking human being. All life and thought are in the end a means of progress towards self-realisation and God-realisation. Indian religion never considered intellectual or theological conceptions about the supreme Truth to be the one thing of central importance. To pursue that Truth under whatever conception or whatever form, to attain to it by inner experience, to live in it in consciousness, this it held to be the sole thing needful. One school or sect might consider the real self of man to be indivisibly one with the universal Self or the supreme Spirit. Another might regard man as one with the Divine in essence but different from him in Nature. A third might hold God, Nature and the individual soul in man to be three eternally different powers of being. But for all the truth of Self held with equal force; for even to the Indian dualist, God is the supreme self and reality in whom and by whom Nature and man live, move and have their being and, if you eliminate God from his view of things, Nature and man would lose for him all their meaning and importance. The Spirit, universal Nature (whether called Maya, Prakriti or Shakti) and the soul in living beings, Jiva, are the three truths which are universally admitted by all the many religious sects and conflicting religious philosophies of India. Universal also is the admission that the discovery of the inner spiritual self in man, the divine soul in him, and some kind of living and uniting con- tact or absolute unity of the soul in man with God or supreme Self or eternal Brahman is the condition of spiritual perfection. Page-126

It is open to us to conceive

and have experience of the Divine as an impersonal Absolute and Infinite or to

approach and know and feel Him as a transcendent and universal sempiternal

Person: but whatever be our way of reaching him, the one important truth of

spiritual experience is that he is in the heart and centre of all existence and

all existence is in him and to find him is the great self-finding. Differences

of credal belief are to the Indian mind nothing more than various ways of

seeing the one Self and Godhead in all. Self-realisation is the one thing

needful; to open to the inner Spirit, to live in the Infinite, to seek after

and discover the Eternal, to be in union with God, that is the common idea and

aim of religion, that is the sense of spiritual salvation, that is the living

Truth that fulfils and releases. This dynamic following after the highest

spiritual truth and the highest spiritual aim are the uniting bond of Indian

religion and, behind all its thousand forms, its one common essence. Page-127

very highest spiritual truth

and some breath of its influence into every part of the religious field.

Nothing can be more untrue than to pretend that the general religious mind of

India has not at all grasped the higher spiritual or metaphysical truths of Indian

religion. It is a sheer falsehood or a wilful misunderstanding to say that it

has lived always in the externals only of rite and creed and shibboleth. On the

contrary, the main metaphysical truths of Indian religious philosophy in their

broad idea-aspects or in an intensely poetic and dynamic representation have

been stamped on the general mind of the people. The ideas of Maya, Lila, divine

Immanence are as familiar to the man in the street and the worshipper in the

temple as to the philosopher in his seclusion, the monk in his monastery and

the saint in his hermitage. The spiritual reality which they reflect, the

profound experience to which they point has permeated the religion, the

literature, the art, even the popular religious songs of a whole people. Page-128

inner realities, are divided

from them by a less thick veil of the universal ignorance and are more easily

led back to a ,vital glimpse of God and Spirit, self and eternity than the mass

of men or even the cultured elite anywhere else. Where else could the

lofty, austere and difficult teaching of a Buddha have seized so rapidly on the

popular mind? Where else could the songs of a Tukaram, a Ramprasad, a Kabir,

the Sikh Gurus and the chants of the Tamil saints with their fervid devotion

but also their pro- found spiritual thinking have found so speedy an echo and

formed a popular religious literature? This strong permeation or close nearness

of the spiritual turn, this readiness of the mind of a whole nation to turn to

the highest realities is the sign and fruit of an agelong, a real and a still

living and supremely spiritual culture. Page-129

have been querulous bickerings

of sects with their pretensions to spiritual superiority and greater knowledge,

and sometimes, at one time especially in southern India in a period of acute

religious differences, there have been brief local outbreaks of active mutual

tyranny and persecution even unto death. But these things have never taken the

proportions which they assumed in Europe. Intolerance has been confined for the

most part to the minor forms of polemical attack or to social obstruction or

ostracism; very seldom have they transgressed across the line to the major

forms of barbaric persecution which draw a long, red and hideous stain across

the religious history of Europe. There has played ever in India the saving

perception of a higher and purer spiritual intelligence, which has had its

effect on the mass mentality. Indian religion has always felt that since the

minds, the temperaments, the intellectual affinities of men are unlimited in

their variety, a perfect liberty of thought and of worship must be allowed to

the individual in his approach to the Infinite. Page-130

enlarging continuity of her

spiritual experience. That ageless continuity was carefully conserved, but it

admitted light from all quarters. In later times the saints who reached some

fusion of the Hindu and the Islamic teaching were freely and immediately

recognised as leaders of Hindu religion,

― even,

in some cases, when they started with a Mussulman birth and from the Mussulman

standpoint. The Yogin who developed a new path of Yoga, the religious teacher

who founded a new order, the thinker who built up a novel statement of the

many-sided truth of spiritual existence, found no serious obstacle to their

practice or their propaganda. At most they had to meet the opposition of the

priest and Pundit instinctively adverse to any change; but this had only to be

lived down for the new element to be received into the free and pliant body of

the national religion and its ever plastic order. Page-131

handed it down from generation

to generation but were empowered also, unlike the priest and the Pundit, to

enrich freely its significance and develop its practice. A living and moving,

not a rigid continuity, was the characteristic turn of the inner religious mind

of India. The evolution of the Vaishnava religion from very early times, its

succession of saints and teachers, the striking developments given to it

successively by Ramanuja, Madhwa, Chaitanya, Vallabhacharya and its recent

stirrings of survival after a period of languor and of some fossilisation form

one notable example of this firm combination of agelong continuity and fixed

tradition with latitude of powerful and vivid change. A more striking instance

was the founding of the Sikh religion, its long line of Gurus and the novel

direction and form given to it by Guru Govind Singh in the democratic

institution of the Khalsa. The Buddhist Sangha

and its councils, the creation of a sort of divided pontifical authority by

Shankaracharya, an authority transmitted from generation to generation for more

than a thousand years and even now not altogether effete, the Sikh Khalsa, the

adoption of the congregational form called Samaj by the modern reforming sects

indicate an attempt towards a compact and stringent order. But it is noteworthy

that even in these attempts the freedom and plasticity and living sincerity of

the religious mind of India always prevented it from initiating anything like

the overblown ecclesiastical orders and despotic hierarchies which in the West

have striven to impose the tyranny of their obscurantist yoke on the spiritual

liberty of the human race. Page-132

with its marvellous wealth of

many-sided philosophies, of great scriptures, of profound religious works, of

religions that approach the Eternal from every side of his infinite Truth, of

Yoga- systems of psycho-spiritual discipline and self-finding, of suggestive

forms, symbols and ceremonies, which are strong to train the mind at all stages

of development towards the Godward endeavour. Its firm structure capable of

supporting without peril a large tolerance and assimilative spirit, its

vivacity, intensity, profundity and multitudinousness of experience, its

freedom from the unnatural European divorce between mundane know- ledge and

science on the one side and religion on the other, its reconciliation of the

claims of the intellect with the claims of the spirit, its long endurance and

infinite capacity of revival make it stand out today as the most remarkable,

rich and living of all religious systems. The nineteenth century has thrown on

it its tremendous shock of negation and scepticism but has not been able to destroy

its assured roots of spiritual knowledge. A little disturbed for a brief

moment, surprised and temporarily shaken by this attack in a period of greatest

depression of the nation's vital force, India revived almost at once and

responded by a fresh outburst of spiritual activity, seeking, assimilation,

formative effort. A great new life is visibly preparing in her, a mighty

transformation and farther dynamic evolution and potent march forward into the

inexhaustible infinities of spiritual experience. Page-133

limits; but, after all, it is

perhaps safest to do without these dangerous spices. Trained in these

conceptions, the European critic comes to India and is struck by the immense

mass and intricacy of a polytheistic cult crowned at its summit by a belief in

the one Infinite. This belief he erroneously supposes to be identical with the

barren and abstract intellectual pantheism of the West. He applies with an

obstinate prejudgment the ideas and definitions of his own thinking, and this

illegitimate importation has fixed many false values on Indian spiritual

conceptions, ―

unhappily, even in the mind of "educated" India. But

where our religion eludes his fixed standards, misunderstanding, denunciation

and supercilious condemnation come. at once to his rescue. The Indian mind, on

the contrary, is averse to intolerant mental exclusions; for a great force of

intuition and inner

experience had given it from the beginning that towards which the mind of the

West is only now reaching with much fumbling and difficulty,

― the cosmic

consciousness, the cosmic vision. Even when it sees the One without a second,

it still admits his duality of Spirit and Nature; it leaves room for his many trinities

and million aspects. Even when it concentrates on a single limiting aspect of

the Divinity and seems to see nothing but that, it still keeps instinctively at

the back of its conscious- ness the sense of the All and the idea of the One.

Even when it distributes its worship among many objects, it looks at the same

time through the objects of its worship and sees beyond the multitude of

godheads the unity of the Supreme. This synthetic turn is not peculiar to the

mystics or to a small literate class or to philosophic thinkers nourished on

the high sublimities of the Veda and Vedanta. It permeates the popular mind

nourished on the thoughts, images, traditions, and cultural symbols of the

Purana and Tantra; for these things are only concrete representations or living

figures of the synthetic monism, the many-sided unitarianism, the large cosmic

universalism of the Vedic scriptures. Page-134 names and powers and personalities of the Eternal and Infinite. A colourless monism or a pale vague transcendental Theism was not its beginning, its middle and its end. The one Godhead is worshipped as the All, for all in the universe is he or made out of his being or his nature. But Indian religion is not therefore pantheism; for beyond this universality it recognises the supracosmic Eternal. Indian polytheism is not the popular polytheism of ancient Europe; for here the worshipper of many gods still knows that all his divinities are forms, names, personalities and powers of the One; his gods proceed from the one Purusha, his goddesses are energies of the one divine Force. Those ways of Indian cult which most resemble a popular form of Theism, are still something more; for they do not exclude, but admit the many aspects of God. Indian image-worship is not the idolatry of a barbaric or undeveloped mind, for even the most ignorant know that the image is a symbol and support and can throw it away when its use is over. The later religious forms which most felt the impress of the Islamic idea, like Nanak's worship of the timeless One, Akala, and the reforming creeds of today, born under the influence of the West, yet draw away from the limitations of western or Semitic monotheism. Irresistibly they turn from these infantile conceptions towards the fathomless truth of Vedanta. The divine Personality of God and his human relations with man are strongly stressed by Vaishnavism and Shaivism as the most dynamic Truth; but that is not the whole of these religions, and this divine Personality is not the limited magnified- human personal God of the. West. Indian religion cannot be described by any of the definitions known to the occidental intelligence. In its totality it has been a free and tolerant synthesis of all spiritual worship and experience. Observing the one Truth from all its many sides, it shut out none. It gave itself no specific name and bound itself by no limiting distinction. Allowing separative designations for its constituting cults and divisions, it remained itself nameless, formless, universal, infinite, like the Brahman of its agelong seeking. Although strikingly distinguished from other creeds by its traditional scriptures, cults and symbols, it is not in its essential character a credal religion at all but a vast and many-sided, an always unifying and always pro- Page-135

gressive and self-enlarging

system of spiritual culture.1

1 The only religion that India has apparently rejected in the end is Buddhism; but in fact this appearance is a historical error. Buddhism lost its separative force, because its spiritual substance, as opposed to its credal parts, was absorbed by the religious mind of Hindu India. Even so, it survived in the North and was exterminated not by Shankaracharya or another, but by the invading force of Islam Page-136

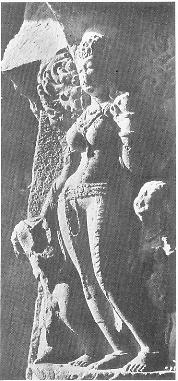

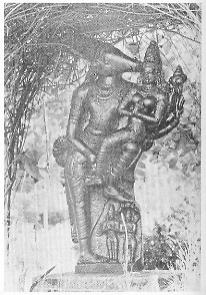

approach the Infinite; all cosmic

powers are manifestations, all forces are forces of the One. The gods behind

the workings of Nature are to be seen and adored as powers, names and

personalities of the one Godhead. An infinite Conscicous-Force, executive

Energy, Will or Law, Maya, Prakriti, Shakti or Karma, is behind all happenings,

whether to us they seem good or bad, acceptable or unacceptable, fortunate or

adverse. The Infinite creates and is Brahma; it preserves and is Vishnu; it

destroys or takes to itself and is Rudra or Shiva. The supreme Energy

beneficent in upholding and protection is or else formulates itself as the

Mother of the worlds, Luxmi or Durga. Or beneficent even in the mask of

destruction it is Chandi or it is Kali, the dark Mother. The One Godhead

manifests himself in the form of his qualities in various names and godheads.

The God of divine love of the Vaishnava, the God of divine power of the Shakta

appear as two different godheads; but in truth they are the one infinite Deity

in different figures.1 One may approach

the Supreme through any of these names and forms, with knowledge or in

ignorance; for through them and beyond them we can proceed at last to the

supreme experience.

1 This explanation of Indian polytheism is not a modern invention created to meet western reproaches; it is to be found explicitly stated in the Gita; it is, still earlier, the sense of the Upanishads; it was clearly stated in so many words in the first ancient days by the "primitive" poets (in truth the profound mystics) of the Veda. Page-137 plane of consciousness he can reach is determined by, the inner evolutionary stage. Thence comes the variety of religious cult, but its data are not imaginary structures, inventions of priests or poets, but truths of a supraphysical existence intermediate between the consciousness of the physical world and the ineffable superconscience of the Absolute. The idea of strongest consequence at the base of Indian religion is the most dynamic for the inner spiritual life. It is that while the Supreme or the Divine can be approached through a universal consciousness and by piercing through all inner and outer Nature, That or He can be met by each individual soul in itself, in its own spiritual part, because there is something in it that is intimately one or at least intimately related with the one divine Existence. The essence of Indian religion is to aim at so growing and so living that we can grow out of the Ignorance which veils this self-knowledge from our mind and life and be- come aware of the Divinity within us. These three things put together are the whole of Hindu religion, its essential sense and, if any credo is needed, its credo. Page-138 2

THE task of religion and spirituality is to mediate between God and man, between the Eternal and Infinite and this transient, yet persistent finite, between a luminous Truth-Consciousness not expressed or not yet expressed here and the Mind's ignorance. But nothing is more difficult than to bring home the greatness and uplifting power of the spiritual consciousness to the natural man forming the vast majority of the race; for his mind and senses, are turned outward towards the external calls of life and its objects and never inwards to the Truth which lies behind them. This external vision and attraction are the essence of the universal blinding force which is designated in Indian philosophy the Ignorance. Ancient Indian spirituality recognised that man lives in the Ignorance and has to be led through its imperfect indications to a highest inmost knowledge. Our life moves between two worlds, the depths upon depths of our inward being and the surface field of our outward nature. The majority of men put the whole emphasis of life on the outward and live very strongly in their surface consciousness and very little in the inward existence. Even the choice spirits raised from the grossness of the common vital and physical mould by the stress of thought and culture do not usually get farther than a strong dwelling on the things of the mind. The highest flight they reach ― and it is this that the West persistently mistakes for spirituality ― is a preference for living in the mind and emotions more than in the gross outward life or else an attempt to subject this rebellious life-stuff to the law of intellectual truth or ethical reason and will or aesthetic beauty or of all three together. But spiritual knowledge perceives that there is a greater thing in us; our inmost self, our real being is not the intellect, not the aesthetic, ethical or thinking mind, but the divinity within, the Spirit, and these other things are only the instruments of the Spirit. A mere intellectual, ethical and aesthetic culture does not go back to the inmost truth of the spirit; it is still an Ignorance, an incomplete, outward and super- Page-139

ficial knowledge. To have made

the discovery of our deepest being and hidden spiritual nature is the first

necessity and to have erected the living of an inmost spiritual life into the

aim of existence is the characteristic sign of a spiritual culture. Page-140 towards this aim; in spite of all the difficulties, imperfections and fluctuations of its evolution, it had this character. But like other cultures it was not at all times and in all its parts and movements consciously aware of its own total significance. This large sense sometimes emerged into something like a conscious synthetic clarity, but was more often kept in the depths and on the surface dispersed in a multitude of subordinate and special standpoints. Still, it is only by an intelligence of the total drift that its manifold sides and rich variations of effort and teaching and discipline can receive their full reconciling unity and be understood in the light of its own most intrinsic purpose. Now the spirit of Indian religion and spiritual culture has been persistently and immovably the same throughout the long time of its vigour, but its form has undergone remarkable changes. Yet if we look into them from the right centre it will be apparent that these changes are the results of a logical and inevitable evolution inherent in the very process of man's growth towards the heights. In its earliest form, its first Vedic system, it took its outward foundation on the mind of the physical man whose natural faith is in things physical, in the sensible and visible objects, presences, representations and the external pursuits and aims of the material world. The means, symbols, rites, figures, by which it sought to mediate between the spirit and the normal human mentality were drawn from these most external physical things. Man's first and primitive idea of the Divine can only come through his vision of external Nature and the sense of a superior Power or Powers concealed behind her phenomena veiled in the heaven and earth, father and mother of our being, in the sun and moon and stars, its lights and regulators, in dawn and day and night and rain and wind and storm, the oceans and the rivers and the forests, all the circumstances and forces of her scene of action, all that vast and mysterious surrounding life of which we are a part and in which the natural heart and mind of the human creature feel instinctively through whatever bright or dark or confused figures that there is here some divine Multitude or else mighty Infinite, one, manifold and mysterious, which takes these forms and manifests itself in these motions. The Vedic religion took this natural sense and feeling of the physical man; Page-141 it used the conceptions to which they gave birth, and it sought to lead him through them to the psychic and spiritual truths of his own being and the being of the cosmos. It recognised that he was right when he saw behind the manifestations of Nature great living powers and godheads, even though he knew not their inner truth, and right too in offering to them worship and propitiation and atonement. For that inevitably must be the initial way in which his active physical, vital and mental nature is allowed to approach the Godhead. He approaches it through its visible outward manifestations as something greater than his own natural self, something single or multiple that guides, sustains and directs his life, and he calls to it for help and support in the desires and difficulties and distresses and struggles of his human existence.1 () The Vedic religion accepted also the form in which early man everywhere expressed his sense of the relation between himself and the godheads of Nature; it adopted as its central symbol the act and ritual of a physical sacrifice. However crude the notions attached to it, this idea of the necessity of sacrifice did express obscurely a first law of being. For it was founded on that secret of constant interchange between the individual and the universal powers of the cosmos which covertly supports all the process of life and develops the action of Nature. But even in its external and exoteric side the Vedic religion did not limit itself to this acceptance and regulation of the first religious notions of the natural physical mind of man. The Vedic Rishis gave a psychic function to the godheads worshipped by the people; they spoke to them of a higher Truth, Right, Law of which the gods were the guardians, of the necessity of a truer knowledge and a larger inner living according to this Truth and Right, and of a home of Immortality to which the soul of man could ascend by the power of Truth and of right doing. The people no doubt took these ideas in their most external sense; but they were trained by them to develop their ethical

1 The Gita recognises four kinds of degrees of worshippers and God-seekers: There are first the artharthi and ārta, those who seek him for the fulfilment of desire and those who turn for divine help in the sorrow and suffering of existence; there is next the jijñāsu, the seeker of knowledge, the questioner who is moved to seek the Divine in his truth and in that to meet him; last and highest, there is the jñāni who has already contact with the truth and is able to live in unity with the Spirit. Page-142

nature, to turn towards some initial development of their psychic being, to

conceive the idea of a knowledge and truth other than that of the physical life

and to admit even a first conception of some greater spiritual Reality which

was the ultimate object of human worship or aspiration. This religious and

moral force was the highest reach of the external cult and the most that could

be understood or followed by the mass of the people. Page-143 foundation of all our culture to the Rishis, whatever its fabulous forms

and mythical ascriptions, contains a real truth and veils a sound historic

tradition. It reflects the fact of a true initiation and an unbroken continuity

between this great primitive past and the riper but hardly greater spiritual

development of our historic culture. Page-144 This is the aspect of the Vedic teaching and worship to which a European

scholar, mistaking entirely its significance because he read it in the dim and

poor light of European religious experience, has given the sounding misnomer,

henotheism. Beyond, in the triple Infinite, these godheads put on their highest

nature and are names of the one nameless Ineffable. Page-145 forms, names, powers, personalities of his Godhead. There is the distinction between the Knowledge and the Ignorance,1 () the greater truth of an immortal life opposed to the much falsehood or mixed truth and falsehood of mortal existence. There is the discipline of an inward growth of man from the physical through the psychic to the spiritual existence. There is the conquest of death, the secret of immortality, the perception of a realisable divinity of the human spirit. In an age to which in the insolence of our external knowledge we are accustomed to look back as the childhood of humanity or at best a period of vigorous barbarism, this was the inspired and intuitive psychic and spiritual teaching by which the ancient human fathers, purve pitarah manuŞyāh, founded a great and profound civilisation in India. This high beginning was secured in its results by a larger sublime efflorescence. The Upanishads have always been recognised in India as the crown and end of the Veda; that is indicated in their general name, Vedanta. And they are in fact a large crowning outcome of the Vedic discipline and experience. The time in which the Vedantic truth was wholly seen and the Upanishads took shape, was, as we can discern from such records as the Chhandogya and Brihadaranyaka, an epoch of immense and strenuous seeking, an intense and ardent seed-time of the Spirit. In the stress of that seeking the truths held by the initiates but kept back from ordinary men broke their barriers, swept through the higher mind of the nation and fertilised the soil of Indian culture for a constant and ever-increasing growth of spiritual consciousness and spiritual experience. This turn was not as yet universal; it was chiefly men of the higher classes, Kshatriyas and Brahmins trained in the Vedic system of education, no longer content with an external truth and the works of the outer sacrifice, who began everywhere to seek for the highest word of revealing experience from the sages who possessed the knowledge of the One. But we find too among those who attained to the knowledge and became great teachers men of inferior or doubtful birth like Janashruti, the wealthy Shudra, or Satyakama Jabali, son of a servant-girl who knew not who was his father. The work

1 Cittim acittim cinavad vi vidvān: "Let the knower distinguish the Knowledge and the Ignorance." Page-146 that was done in this period became the firm bedrock of Indian

spirituality in later ages and from it gush still the life-giving waters of a

perennial never-failing inspiration. This period, this activity, this grand

achievement created the whole difference between the evolution of Indian civilisation

and the quite different curve of other cultures. Page-147 a highest and most direct and powerful language of intuition and inner

experience. It was not the language of the intellect, but still it wore a form

which the intellect could take hold of, translate into its own more abstract

terms and convert into a a starting-point for an ever-widening and deepening

philosophic speculation and the reason's long search after a Truth original,

supreme and ultimate. There was in India as in the West a great upbuilding of a

high, wide and complex intellectual, aesthetic, ethical and social culture. But

left in Europe to its own resources, combated rather than helped by an obscure

religious emotion and dogma, here it was guided, uplifted and more and more

penetrated and suffused by a great saving power of spirituality and a vast

stimulating and tolerant light of wisdom from a highest ether of knowledge. Page-148 these matters. There was a constant admission that spiritual experience

is a greater thing and its light a truer if more incalculable guide than the

clarities of the reasoning intelligence. Page-149 ponding potent stress on spiritual asceticism as the higher way. The two

trends, on one side an extreme of the richness of life experience, on the other

an extreme and pure rigorous intensity of the spiritual life, accompanied each

other; their interaction, whatever loss there might be of the earlier deep

harmony and large synthesis, yet by their double pull preserved something still

of the balance of Indian culture.

1 Buddha himself does not seem to have preached his tenets as a novel revolutionary creed, but as the old Aryan way, the true form of the eternal religion. Page-150 and spiritual positions. A result of an intense stress of the union of logical reason with the spiritualised mind, ― for it was by an intense spiritual seeking supported on a clear and hard rational thinking that it was born as a separate religion, ― its trenchant affirmations and still more exclusive negations could not be made sufficiently compatible with the native flexibility, many- sided susceptibility and rich synthetic turn of the Indian religious consciousness; it was a high creed but not plastic enough to hold the heart of the people. Indian religion absorbed all that it could of Buddhism, but rejected its exclusive positions and preserved the full line of its own continuity, casting back to the ancient Vedanta. This lasting line of change moved forward not by any destruction of principle, but by a gradual fading out of the prominent Vedic forms and the substitution of others. There was a transformation of symbol and ritual and ceremony or a substitution of new kindred figures, an emergence of things that are only hints in the original system, a development of novel idea forms from the seed of the original thinking. And especially there was a farther widening and fathoming of psychic and spiritual experience. The Vedic gods rapidly lost their deep original significance. At first they kept their hold by their outer cosmic sense but were overshadowed by the great Trinity, Brahma- Vishnu-Shiva, and afterwards faded altogether. A new pantheon appeared which in its outward symbolic aspects expressed a deeper truth and larger range of religious experience, an intenser feeling, a vaster idea. The Vedic sacrifice persisted only in broken and lessening fragments. The house of Fire was replaced by the temple; the karmic ritual of sacrifice was transformed into the devotional temple ritual; the vague and shifting mental images of the Vedic gods figured in the Mantras yielded to more precise conceptual forms of the two great deities, Vishnu and Shiva, and of their Shaktis and their offshoots. These new concepts stabilised in physical images were made the basis both for internal adoration and for the external worship which replaced sacrifice. The psychic and spiritual mystic endeavour which was the inner sense of the Vedic hymns, disappeared into the less intensely luminous but more wide and rich and complex Page-151

psycho-spiritual inner life of

Puranic and Tantric religion and Yoga. Page-152 religious to a profounder psychic-spiritual truth and experience. Nothing essential was touched in its core by this new orientation; but the instruments, atmosphere, field of religious experience underwent a considerable change. The Vedic godheads were to the mass of their worshippers divine powers who presided over the workings of the outward life of the physical cosmos; the Puranic Trinity had even for the multitude a predominant psycho-religious and spiritual significance. Its more external significance, for instance, the functions of cosmic creation, preservation and destruction, were only a dependent fringe of these profundities that alone touched the heart of its mystery. The central spiritual truth remained in both systems the same, the truth of the One in many aspects. The Trinity is a triple form of the one supreme Godhead and Brahman; the Shaktis are energies of the one Energy of the highest divine Being. But this greatest religious truth was no longer reserved for the initiated few; it was now more and more brought powerfully, widely and intensely home to the general mind and feeling of the people. Even the so-called henotheism of the Vedic idea was prolonged and heightened in the larger and simpler worship of Vishnu or Shiva as the one universal and highest Godhead of whom all others are living forms and powers. The idea of the Divinity in man was popularised to an extraordinary extent, not only the occasional manifestation of the Divine in humanity which founded the worship of the Avataras, but the Presence discoverable in the heart of every creature. The systems of Yoga developed themselves on the same common basis. All led or hoped to lead through many kinds of psycho-physical, inner vital, inner mental and psycho-spiritual methods to the common aim of all Indian spirituality, a greater consciousness and a more or less complete union with the One and Divine or else an immergence of the individual soul in the Absolute. The Purano-Tantric system was a wide, assured and many-sided endeavour, unparalleled in its power, insight, amplitude, to provide the race with a basis of generalised psycho-religious experience from which man could rise through knowledge, works or love or through any other fundamental power of his nature to some established supreme experience and highest absolute status. Page-153 This great effort and achievement which covered all the time between the Vedic age and the decline of Buddhism, was still not the last possibility of religious evolution open to Indian culture. The Vedic training of the physically-minded man made the development possible. But in its turn this raising of the basis of religion to the inner mind and life and psychic nature, this training and bringing out of the psychic man ought to make possible a still larger development and support a greater spiritual movement as the leading power of life. The first stage makes possible the preparation of the natural external man for spirituality; the second takes up his outward life into a deeper mental and psychical living and brings him more directly into contact with the spirit and divinity within him; the third should render him capable of taking up his whole mental, psychical, physical living into a first beginning at least of a generalised spiritual life. This endeavour has manifested itself in the evolution of Indian spirituality and is the significance of the latest philosophies, the great spiritual movements of the saints and Bhaktas and an increasing resort to various paths of Yoga. But unhappily it synchronised with a decline of Indian culture and an increasing collapse of its general power and knowledge, and in these surroundings, it could not bear its natural fruit; but at the same time it has done much to prepare such a possibility in the future. If Indian culture is to survive and keep its spiritual basis and innate character, it is in this direction, and not in a mere revival or a prolongation of the Puranic system, that its evolution must turn, rising so towards the fulfilment of that which the Vedic seers saw as the aim of man and his life thousands of years ago and the Vedantic sages cast into the clear and immortal forms of their luminous revelation. Even the psychic-emotional part of man's nature is not the inmost door to religious feeling nor is his inner mind the highest witness to spiritual experience. There is behind the first the inmost soul of man, in that deepest secret heart, hrdaye guhãyãm, in which the ancient seers saw the very tabernacle of the indwelling Godhead, and there is above the second a luminous highest mind directly open to a truth of the Spirit to which man's normal nature has as yet only an occasional and momentary access. Religious evolution, spiritual experience can find their true native road only when Page-154

they open to these hidden

powers and make them their support for a lasting change, a divinisation of

human life and nature. An effort of this kind was the very force behind the

most luminous and vivid of the later movements of India's vast religious

cycles. It is the secret of the most powerful forms of Vaishnavism and Tantra

and Yoga. The labour of ascent from our half animal human nature into the

fresh purity of the spiritual consciousness needed to be followed and

supplemented by a descent of the light and force of the spirit into man's

members and the attempt to transform human into divine nature. Page-155 3

IT IS essential, if we are to get a right view of Indian civilisation or of any civilisation, to keep to the central, living, governing things and not to be led away by the confusion of accidents and details. This is a precaution which the critics of our culture steadily refuse to take. A civilisation, a culture must be looked at first in its initiating, supporting, durable central motives, in its heart of abiding principle; otherwise we shall be likely to find ourselves, like these critics, in a maze without a clue and we shall stumble about among false and partial conclusions and miss entirely the true truth of the matter. The importance of avoiding this error is evident when we are seeking for the essential significance of Indian religious culture. But the same method must be held to when we proceed to observe its dynamic formulation and the effect of its spiritual ideal on life. Indian culture recognises the spirit as the truth of our being and our life as a growth and evolution of the spirit. It sees the Eternal, the Infinite, the Supreme, the All; it sees this as the secret highest Self of all, this is what it calls God, the Permanent, the Real, and it sees man as a soul and power of this being of God in Nature. The progressive growth of the finite conscious- ness of man towards this Self, towards God, towards the universal, the eternal, the infinite, in a word his growth into spiritual consciousness by the development of his ordinary ignorant natural being into an illumined divine nature, this is for Indian thinking the significance of life and the aim of human existence. To this deeper and more spiritual idea of Nature and of existence a great deal of what is strongest and most potential of fruitful consequences in recent European thinking already turns with a growing impetus. This turn may be a relapse to "barbarism" or it may be the high natural outcome of her own increasing and ripened culture; that is a question for Europe to decide. But always to India this ideal inspiration or rather this spiritual vision of Self, God, Spirit, this nearness to a cosmic consciousness, a cosmic sense and feeling, a cosmic idea, will, love, delight into Page-156

which we can release the

limited, ignorant suffering ego, this drive towards the transcendental,

eternal and infinite, and the moulding of man into a conscious soul and power

of that greater Existence have been the engrossing motive of her philosophy,

the sustaining force of her religion, the fundamental idea of her civilisation

and culture. Page-157

and by that too hasty

imagination falls short in his endeavour. Its index vision is pointed to a

truth that exceeds the human mind and, if at all realised in his members, would

turn human life into a divine super-life. And not until this third largest

sweep of the spiritual evolution has come into its own, can Indian civilisation

be said to have discharged its mission, to have spoken ... its last word and be functus officio, crowned

and complete in its office of mediation between the life of man and the spirit. Page-158

both of man's inner and his

outer existence. Page-159

side of the cultural effort

took the form of an endeavour to cast the whole of life into a religious mould;

it multiplied means and devices which by their insistent suggestion and

opportunity and their mass of effect would help to stamp a Godward tendency on

the entire existence. Indian culture was founded on a religious conception of

life and both the individual and the community drank in at every moment its

influence. It was stamped on them by the training and turn of the education;

the entire life

atmosphere, all the social surroundings were

suffused with it; it

breathed its power through the whole original form and

hieratic character of the culture. Always was felt the near idea of the

spiritual existence and its supremacy as the ideal, highest over all others;

everywhere there was the pervading pressure of the notion of the universe as a

manifestation of divine Powers and a movement full of the presence of the

Divine. Man himself was not a mere reasoning animal, but a soul in constant

relation with God and with the divine cosmic Powers. The soul's continued

existence was a cyclic or upward progress from birth to birth; human life was

the summit of an evolution which terminated in the conscious Spirit, every

stage of that life a step in a pilgrimage. Every single action of man had its

importance of fruit whether in future lives or in the worlds beyond the

material existence. Page-160

of

human nature, every characteristic turn of its action was given a place in the

system; each was suitably surrounded with' the spiritual idea and a religious

influence, each provided with steps by which it might rise towards its own

spiritual possibility and significance. The highest spiritual meaning of life

was set on the summits of each evolving power of the human nature. The

intelligence was called to a supreme knowledge, the dynamic active and creative

powers pointed to openness and unity with an infinite and universal Will, the

heart and sense put in contact with a divine love and joy and beauty. But

this-highest meaning was also put everywhere indicatively or in symbols behind

the whole system of living, even in its details, so that its impression might

fall in whatever degree on the life, increase in pervasion and in the end take

up the entire control. This was the aim and, if we consider the imperfections

of our nature and the difficulty of the endeavour, we can say that it achieved

an unusual measure of success. It has been said with some truth that for the

Indian the whole of life is a religion. True of the ideal of Indian life, it is

true to a certain degree and in a certain sense in its fact and practice. No

step could be taken in the Indian's inner or outer life without his being

reminded of a spiritual existence. Everywhere he felt the closeness or at least

saw the sign of something beyond his natural life, beyond the moment in time,

beyond his individual ego, something other than the needs and interests of his

vital and physical nature. That insistence gave its tone and turn to his

thought and action and feeling; it produced that subtler sensitiveness to the

spiritual appeal, that greater readiness to turn to the spiritual effort which

are even now the distinguishing marks of the Indian temperament. It is that

readiness, that sensitiveness which justifies us when we speak of the

characteristic spirituality of the Indian people. Page-161 response. There is presented to our view for all our picture of life the sharp division of two extremes; the saint and the worldling, the religious and the irreligious, the good and the bad, the pious and the impious, souls accepted and souls rejected, the sheep and the goats, the saved and the damned, the believer and the infidel, are the two categories set constantly before us. All between is a confusion, a tug of war, an uncertain balance. This crude and summary classification is the foundation of the Christian system of an eternal heaven and hell; at best, the Catholic religion humanely interposes a precarious chance hung between that happy and this dread alternative, the chance of a painful purgatory for more than nine-tenths of the human race. Indian religion set up on its summits a still more high-pitched spiritual call, a standard of conduct still more perfect and absolute; but it did not go about its work with this summary and unreflecting ignorance. All beings are to the Indian mind portions of the Divine, evolving souls, and sure of an eventual salvation and release into the spirit. All must feel, as the good in them grows or, more truly, the godhead in them finds itself and becomes conscious, the ultimate touch and call of their highest self and through that call the attraction to the Eternal and the Divine. But actually in life there are infinite differences between man and man; some are more inwardly evolved, others are less mature, many if not most are infant souls incapable of great steps and difficult efforts. Each needs to be dealt with according to his nature and his soul stature. But a general distinction can be drawn between three principal types varying in their openness to the spiritual appeal or to the religious influence or impulse. This distinction amounts to a gradation of three stages in the growing human consciousness. One crude, ill-formed, still outward, still vitally and physically minded can be led only by devices suited to its ignorance. Another, more developed and capable of a much stronger and deeper psycho-spiritual experience, offers a riper make of man-hood gifted with a more conscious intelligence, a larger vital or aesthetic opening, a stronger ethical power of the nature. A third, the ripest and most developed of all, is ready for the spiritual heights, fit to receive or to climb towards the loftiest ultimate truth of God and of its own being and to tread the summits of Page-162 divine experience.1

It was to meet the need of the first type or

level that 'Indian religion created that mass of suggestive ceremony and

effective ritual and strict outward rule and injunction and all that pageant of

attracting and compelling symbol with which the cult is so richly equipped or

profusely decorated. These are for the most part forming and indicative things

which work upon the mind consciently and subconsciently and prepare it for an

entry into the significance of the greater permanent things that lie behind

them. And for this type too, for its vital mind and will, is in- tended all in

the religion that calls on man to turn to a divine Power or powers for the just

satisfaction of his desires and his interests, just because subject to the

right and the law, the Dharma. In the Vedic times the outward ritual sacrifice

and at a later period all the religious forms and notions that clustered

visibly around the rites and imagery of temple worship, constant festival and

ceremony and daily act of outward devotion were intended to serve this type or

this soul-stage. Many of these things may seem to the developed mind to belong

to an ignorant or half-awakened religionism; but they have their concealed

truth and their psychic value and are indispensable in this stage for the

development and difficult awakening of the soul shrouded in the ignorance of

material Nature.

1 The Tantric distinction is between the animal man, the hero man and the divine man, pasu, vira, deva. Or we may grade the difference according to the three Gunas, - first, the tamasic or rajaso-tamasic man ignorant, inert or moved only in a little light by small motive forces, the rajasic or sattwo-rajasic man struggling with an awakened mind and will towards self-development or self-affirmation, and the sattwic man open in mind and heart and will to the Light, standing at the top of the scale and ready to transcend it. Page-163

inward to a more deeply

psycho-religious experience. Already the mind, heart and will have some

strength to grapple with the difficulties of the relations between the spirit

and life, some urge to satisfy more luminously or more inwardly the rational,

aesthetic and ethical nature and lead them upward towards their own highest

heights; one can begin to train mind and soul towards a spiritual consciousness

and the opening of a spiritual existence. This ascending type of humanity

claims for its use all that large and opulent middle region of philosophic,

psycho-spiritual, ethical, aesthetic and emotional religious seeking which is

the larger and more significant portion of the wealth of Indian culture. At

this stage intervene the philosophical systems, the subtle illumining debates

and inquiries of the thinkers; here are the nobler or more passionate reaches

of devotion, here are held up the higher, ampler or austerer ideals of the

Dharma; here break in the psychical suggestions and first definite urgings of

the eternal and infinite which draw men by their appeal and promise towards the

practice of Yoga. But distinctions are lines that can always be overpassed in the infinite complexity of man's nature and there was no sharp Page-164

and unbridgeable division,

only a gradation, since the actuality or potentiality of the three powers

coexist in all men. Both the middle and the highest significances were near and

present and pervaded the whole system, and the approaches to the highest status

were not absolutely denied to any man, in spite of certain prohibitions: but

these prohibitions broke down in practice or left a way of escape to the man

who felt the call; the call itself was a sign of election. He had only to find

the way and the guide. But even in the direct approach, the principle of

adhikãra,

differing capacity and varying nature,

svabhãva,

was recognised in subtle ways, which it would be beyond my present

purpose to enumerate. One may note as an example the significant Indian, idea

of the iSta-devatã,

the special name,

form, idea of the Divinity which each man may choose for worship and communion

and follow after according to the attraction in his nature and his capacity of

spiritual intelligence. And each of the forms has its outer initial associations

and suggestions for the worshipper, its appeal to the intelligence, psychical,

aesthetic, emotional power in the nature and its highest spiritual significance

which leads through some one truth of the Godhead into the essence of

spirituality. One may note too that in the practice of Yoga the disciple has to

be led through his nature and according to his capacity and the spiritual

teacher and guide is expected to perceive and take account of the necessary

gradations and the individual need and power in his giving of help and

guidance. Many things may be objected to in the actual working of this large

and flexible system and I shall take some note of them when I have to deal with

the weak points or the pejorative side of the culture against which the hostile

critic directs with a misleading exaggeration his missiles. But the principle

of it and the main lines of the application embody a remarkable wisdom,

knowledge and careful observation of human nature and an assured insight into

the things of the spirit which none can question who has considered deeply and

flexibly these difficult matters or had any close experience of the obstacles

and potentialities of our nature in its approach to the concealed spiritual

reality. Page-165 vading intimate connection to that general culture of the life of the human being and his powers which must be the first care of every civilisation worth the name. The most delicate and difficult part of this task of human development is concerned with the thinking being of man, his mind of reason and knowledge. No ancient culture of which we have knowledge, not even the Greek, attached more importance to it or spent more effort on its cultivation. The business of the ancient Rishi was not only to know God, but to know the world and life and to reduce it by knowledge to a thing well understood and mastered with which the reason and will of man could deal on assured lines and on a safe basis of wise method and order. The ripe result of this effort was the Shastra. When we speak of the Shastra nowadays, we mean too often only the religio-social system of injunctions of the middle age made sacrosanct by their mythical attribution to Manu, Parasara and other Vedic sages. But in older India Shastra meant any systematised teaching and science; each department of life, each line of activity, each subject of know- ledge had its science or Shastra. The attempt was to reduce each to a theoretical and practical order founded on detailed observation, just generalisation, full experience, intuitive, logical and experimental analysis and synthesis, in order to enable man to know always with a just fruitfulness for life and to act with the security of right knowledge. The smallest and the greatest things were examined with equal care and attention and each provided with its art and science. The name was given even to the highest spiritual knowledge whenever it was stated not in a mass of intuitive experience and revelatory knowledge as in the Upanishads, but for intellectual comprehension in system and order, - and in that sense the Gita is able to call its profound spiritual teaching the most secret science, guhyatamam sãstram. This high scientific and philosophical spirit was carried by the ancient Indian culture into all its activities. No Indian religion is complete without its outward form of preparatory practice, its supporting philosophy and its Yoga or system of inward practice or art of spiritual living: most even of what seems irrational in it to a first glance, has its philosophical turn and significance. It is this complete under- standing and philosophical character which has given religion in Page-166

India its durable security and

immense vitality and enabled it to resist the acid dissolvent power of modem

sceptical inquiry; whatever is ill-founded in experience and reason, that power

can dissolve, but not the heart and mind of these great teachings. But what we

have more especially to observe is that while Indian culture made a distinction

between the lower and the higher learning, the knowledge of things and the

knowledge of self, it did not put a gulf between them like some religions, but

considered the knowledge of the world and things as a preparatory and a leading

up to the knowledge of Self and God. All Shastra was put under the sanction of

the names of the Rishis, who were in the beginning the teachers not only of

spiritual truth and philosophy,

― and we may note that all Indian philosophy,

even the logic of Nyaya and the atomic theory of the Vaisheshikas, has for its

highest crowning note and eventual object spiritual knowledge and liberation, -

but of the arts, the social, political and military, the physical and psychic

sciences, and every instructor was in his degree respected as a guru or

ãcãrya,

a guide or preceptor of the

human spirit. All knowledge was woven into one and led up by degrees to the one

highest knowledge. Page-167

desires, since that is

necessary for the satisfaction and expansion of life, but not in obeying the

dictates of desire as the law of his being; for in all things there is a

greater law, each has not only its side of interest and desire, but its Dharma

or rule of right practice, satisfaction, expansion, regulation. The Dharma,

then, fixed by the wise in the Shastra is the right thing to observe, the true

rule of action. First in the web of Dharma comes the social law; for man's life

is only initially for his vital, personal, individual self, but much more

imperatively for the community, though most imperatively of all for the

greatest Self one in him- self and in all beings, for God, for the Spirit.

Therefore first the individual must subordinate himself to the communal self,

though by no means bound altogether to efface himself in it as the extremists

of the communal idea imagine. He must Jive according to the law of his nature

harmonised with the law of his social type and class, for the nation and in a

higher reach of his being ― this was greatly stressed by

the Buddhists – for humanity. Thus Jiving and acting he could learn to

transcend the social scale of the Dharma, practise without injuring the basis

of life, the ideal scale and finally grow into the liberty of the spirit, when

rule and duty were not binding because he would then move and act in a highest

free and immortal Dharma of the divine nature.

All these aspects of the Dharma were closely linked up

together in a

progressive unity. Thus, for an example, each of the four orders had its own

social function and ethics, but also an ideal rule for the growth of the pure

ethical being, and every man by observing his Dharma and turning his action

Godwards could grow out of it into the spiritual freedom. But behind all Dharma

and ethics was put, not only as a safeguard but as a light, a religious

sanction, a reminder of the continuity of life and of man's long pilgrimage

through many births, a reminder of the Gods and planes beyond and of the

Divine, and above it all the vision of a last stage of perfect comprehension

and unity and of divine transcendence. Page-168

aesthetic satisfactions of all

kinds and all grades were an important part of the culture. Poetry, the drama,

song, dance, music, the greater and lesser arts were placed under the sanction

of the Rishis and were made instruments of the spirit's culture. A just theory

held them to be initially the means of a pure aesthetic satisfaction and each

was founded on its own basic rule and law, but on that basis and with a perfect

fidelity to it still-raised up to minister to the intellectual, ethical and

religious development of the being. It is notable that the two vast Indian

epics have been considered as much as Dharma-shastras as great historico-mythic

epic narratives, itihãsas.

They are, that is

to say, noble, vivid and puissant pictures of life, but they utter and breathe

throughout their course the law and ideal of a great and high ethical and

religious spirit in life and aim in their highest intention at the idea of the

Divine and the way of the mounting soul in the action of the world. Indian

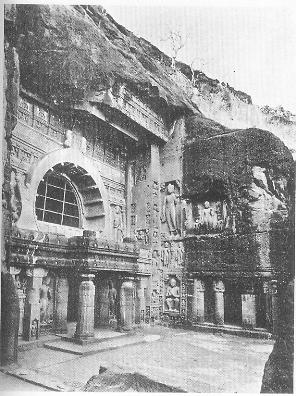

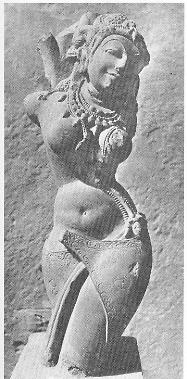

painting, sculpture and architecture did not refuse service to the aesthetic

satisfaction and interpretation of the social, civic and individual life of the

human being; these things, as all evidences show, played a great part in their

motives of creation, but still their highest work was reserved for the greatest

spiritual side of the culture, and throughout we see them seized and suffused

with the brooding stress of the Indian mind on the soul, the Godhead, the

spiritual, the Infinite. And we have to note too that the aesthetic and

hedonistic being was made not only an aid to religion and spirituality and

liberally used for that purpose, but even one of the main gates of man's

approach to the Spirit. The Vaishnava religion especially is a religion of love

and beauty and of the satisfaction of the whole delight-soul of man in God and

even the desires and images of the sensuous life were turned by its vision into

figures of a divine soul-experience. Few religions have gone so far as this

immense catholicity or carried' the whole nature so high in its large, puissant

and many-sided approach to the spiritual and the infinite. Page-169 and enjoyment, military and political rule and conduct and economical well-being. These were directed on one side to success, expansion, opulence and the right art and relation of these activities, but on those motives, demanded by the very nature of the vital man and his action, was imposed the law of the Dharma, a stringent social and ethical ideal and rule, ― thus the whole life of the king as the head of power and responsibility was regulated by it in its every hour and function, - and the constant reminder of religious duty. In later times a Machiavellian principle of statecraft, that which has been always and is still pursued by governments and diplomats, encroached on this nobler system, but in the best age of Indian thought this depravation was condemned as a temporarily effective, but lesser, ignoble and inferior way of policy. The great rule of the culture was that the higher a man's position and power, the larger the scope of his function and influence of his acts and example, the greater should be the call on him of the Dharma. The whole law and custom of society was placed under the sanction of the Rishis and the gods, protected from the violence of the great and powerful, given a socio-religious character and the king himself charged to live and rule as the guardian and servant of the Dharma with only an executive power over the community which was valid so long as he observed with fidelity the Law. And as this vital aspect of life is the one which most easily draws us outward and away from the inner self and the diviner aim of living, it was the most strenuously linked up at every point with the religious idea in the way the vital man can best understand, in the Vedic times by the constant reminder of the sacrifice behind every social and civic act, at a later period by religious rites, ceremonies, worship, the calling in of the gods, the insistence on the subsequent results or a supraterrestrial aim of works. So great was this preoccupation, that while in the spiritual and intellectual and other spheres a considerable or a complete liberty was allowed to speculation, action, creation, here the tendency was to impose a rigorous law and authority, a tendency which in- the end became greatly exaggerated and prevented the expansion of the society into new forms more suitable for the need of the spirit of the age, the Yuga-dharma. A door of liberty was opened to the community Page-170

by the provision of an

automatic permission to change custom and to the individual in the adoption of

the religious life with its own higher discipline or freedom outside the

ordinary social weft of binding rule and injunction. A rigid observation and

discipline of the social law, a larger nobler discipline and freer self-culture

of the ideal side of the Dharma, a wide freedom' of the religious and spiritual

life became the three powers of the system. The steps of the expanding human

spirit mounted through these powers to its perfection. Page-171 4

I

HAVE dwelt at some length, though

still very inadequately, on the principles of Indian religion, the sense of its

evolution and the intention of its system, because these things are being

constantly ignored and battle delivered by its defenders and assailants on

details, particular consequences and side-issues. Those too have their

importance because they are part of the practical execution, the working out of

the culture in life; but they cannot be rightly valued unless we seize hold of

the intention which was behind the execution. And the first thing we see is that

the principle, the essential intention of Indian culture was extraordinarily

high, ambitious and noble, the highest indeed that the human spirit can

conceive. For what can be a greater idea of life tl1an that which makes it a