|

Vyasa: Some Characteristics

THE Mahabharata, although neither the greatest nor the richest masterpiece of the secular literature of India, is at the same time its most considerable and important body of poetry. Being so, it is the pivot on which the history of Sanskrit literature and incidentally the history of Aryan civilisation in India, must perforce turn. To the great discredit of European scholarship the problem of this all-important work is one that remains not only unsolved, but untouched. Yet until it is solved, until the confusion of its heterogeneous materials is reduced to some sort of order, the different layers of which it consists separated, classed and attributed to their relative dates, and its relations with the Ramayana on the one hand and the Puranic and classic literature on the other fully and patiently examined, the history of our civilisation must remain in the air, a field for pedantic wranglings and worthless conjectures. The world knows something of our origins because much labour has been bestowed on the Vedas, something of our decline because post-Buddhistic literature has been much read, annotated and discussed, but of our great medial and flourishing period it knows little, and that little is neither coherent nor reliable. All that we know of the Mahabharata at present is that it is the work of several hands and of different periods — this is literally the limit of the reliable knowledge European scholarship has so far been able to extract from it. For the rest we have to be content with arbitrary conjectures based upon an unwarrantable application of European analogies to Indian things or random assumptions snatched from a word here or a line there, but never proceeding from that weighty, careful and unbiassed study of the work, canto by canto, passage by passage, line by line, which can alone bring us to any valuable conclusions. A fancy was started in Germany that the Iliad of Homer is really a pastiche or clever rifacimento of old ballads put together in the time of Pisistratus. This truly barbarous imagination with its rude

Page – 142 ignorance of the psychological bases of all great poetry has now fallen into some discredit; it has been replaced by a more plausible attempt to discover a nucleus in the poem, an Achilleid, out of which the larger Iliad has grown. Very possibly the whole discussion will finally end in the restoration of a single Homer with a single poem, subjected indeed to some inevitable interpolation and corruption, but mainly the work of one mind, a theory still held by more than one considerable scholar. In the meanwhile, however, haste has been made to apply the analogy to the Mahabharata; lynx-eyed theorists have discovered in the poem — apparently without taking the trouble to study it — an early and rude ballad epic worked up, doctored and defaced by those wicked Brahmins, who are made responsible for all the literary and other enormities which have been discovered by the bushelful, and not by Europeans alone — in our literature and civilisation. A similar method of "arguing from Homer" is probably at the bottom of Professor Weber's assertion that the War Parvas contain the original epic. An observant eye at once perceives that the War Parvas are more hopelessly tangled than any that precede them except the first. It is here and here only that the keenest eye becomes confused and the most confident explorer begins to lose heart and self-reliance. Now whether the theory is true or not, — and one sees nothing in its favour, — it has at present no value at all; for it is a pure theory without any justifying facts. It is not difficult to build these intellectual card-houses. Anyone may raise them by the dozen if he can find no better manner of wasting valuable time. But the Iliad is all battles and it therefore follows in the European mind that the original Mahabharata must have been all battles. Another method is that of ingenious, if forced, argument from stray Slokas of the poem to the equally stray and obscure remarks in Buddhist compilations. The curious theory of some scholars that the Pandavas were a later invention and that the original war was between the Kurus and Panchalas only and Professor Weber's singularly positive inference from a Sloka¹ which does not at first sight bear

¹The Mahabharata, Adiparva, I. 81.

Page – 143 the meaning he puts on it, that the original epic contained only 8,800 verses, are ingenuities of this type. They are based on the Teutonic art of building a whole mammoth out of a single and often problematical bone and remind one strongly of Mr. Pickwick and the historic inscription which was so rudely, if in a Pickwickian sense, challenged by the refractory Mr. Blotton. All these theorisings are idle enough; they are made of too airy a stuff to last. Yet to extricate the original epic from the mass of accretions is not, I believe, so difficult a task as it may at first appear. One is struck in perusing the Mahabharata by the presence of a mass of poetry which bears the style and impress of a single, strong and original, even unusual mind, differing in his manner of expression, tone of thought and stamp of personality not only from every other Sanskrit poet we know, but from every other great poet known to literature. When we look more closely into the distribution of this peculiar style of writing, we come to perceive certain very suggestive and helpful facts. We realise that this impress is only found in those parts of the poem which are necessary to the due conduct of the story; seldom to be detected in the more miraculous, Puranistic or trivial episodes, but usually broken up by passages and sometimes shot through with lines of a discernibly different inspiration. Equally noteworthy is it that nowhere does this part admit any trait, incident or speech which deviates from the strict propriety of dramatic characterisation and psychological probability. Finally, in this body, Krishna's divinity is recognised but more often hinted at than aggressively stated. The tendency is to keep it in the background as a fact to which, while himself crediting it, the writer does not hope for a universal consent, still less is able to speak of it as a general tenet and matter of dogmatic belief; he prefers to show Krishna rather in his human character, acting always by wise, discerning and inspired methods, but still not transgressing the limit of human possibility. All this leads one to the conclusion that in the body of poetry I have described, we have the real Bharata, an epic which tells plainly and straight-forwardly of the events which led to the great war and the empire of the Bharata princes. Certainly, if Professor Weber's venture-

Page – 144 some assertion as to the length of the original Mahabharata be correct, this conclusion falls to the ground; for the mass of this poetry amounts to considerably over 20,000 Slokas. Professor Weber's inference, however, is worth some discussion; for the length of the original epic is a very important element in the problem. If we accept it we must say farewell to all hopes of unravelling the tangle. His assertion is founded on a single and obscure verse in the huge prolegomena to the poem which takes up the greater part of the Adiparva, no very strong basis for so far-reaching an assumption. The Sloka itself says no more than this that much of the Mahabharata was written in so difficult a style that Vyasa himself could remember only 8,800 of the Slokas, Suka an equal amount and Sanjaya perhaps as much, perhaps something less. There is certainly here no assertion such as Prof. Weber would have us find in it that the Mahabharata at any time amounted to no more than 8,800 Slokas. Even if we assume what the text does not say that Vyasa, Suka and Sanjaya knew the same 8,800 Slokas, we do not get to that conclusion. The point simply is that the style of the Mahabharata was too difficult for a single man to keep in memory more than a certain portion of it. This does not carry us very far. Following the genius of the Sanskrit language we are led to suppose the repetition was intended to relate astau ślokasahasrāni etc. with each name, otherwise the repetition has no raison d'être and it is otiose and inept. But if we understand it thus, the conclusion is irresistible that each knew a different 8,800. The writer would have no object in wishing us to repeat the number three times in our mind. If, however, we are to assume that this verse means more than meets the eye, that it is a cryptic way of stating the length of the original poem — and I do not deny that this is possible, perhaps even probable — we should note the repetition of vetti — aham vedmi śuko vetti sañjayo vetti vā na vā. The length of the epic as derived from this single Sloka should then be 26,000 Slokas or less, for the writer hesitates about the exact number to be attributed to Sanjaya. Another passage farther on in the prolegomena agrees remarkably with this conclusion and is in itself much more explicit. It is there stated plainly enough that Vyasa first wrote the Mahabharata in 24,000 Slokas and afterwards enlarged

Page – 145 it to 100,000 for the world of man as well as a still more unconscionable number of verses for the Gandharva and other worlds.¹ In spite of the embroidery of fancy, of a type familiar enough to all who are acquainted with the Puranic method of recording facts, the meaning of this is unmistakable. The original Mahabharata consisted of 24,000 Slokas; but in its final form it runs to 100,000. The figures are probably loose and slovenly, for at any rate the first form of the Mahabharata is considerably under 100,000 Slokas. It is possible therefore that the original epic was something over 24,000 and under 26,400 Slokas, in which case the two passages would agree well enough. But it would be unsafe to found any dogmatic assertion on isolated couplets; at the most we can say that we are justified in taking the estimate as a probable and workable hypothesis and if it is found to be corroborated by other facts, we may venture to suggest its correctness as a moral certainty. This body of poetry then, let us suppose, is the original Mahabharata. Tradition attributes it to Krishna of the Island called Vyasa who certainly lived about this time and was an editor of the Vedas; and since there is nothing in this part of the poem which makes the tradition impossible and much which favours it, we may as a matter both of convenience and of possibility accept it at least provisionally. Whether these hypotheses can be upheld is a question for long and scrupulous consideration and analysis. In this article I wish to formulate, assuming their validity, the larger features of poetical style, the manner of thought and creation and the personal note of Vyasa. Vyasa is the most masculine of writers. When Coleridge spoke of the femineity of genius he had in mind certain features of temperament which, whether justly or not, are usually thought to count for more in the feminine mould than in the masculine, the love of ornament, emotionalism, mobile impressionability, the tyranny of imagination over the reason, excessive sensitiveness to form and outward beauty, tendency to be dominated imaginatively by violence and the show of strength; to be prodigal of oneself, not to husband the powers, to be for showing them off, to fail in self-restraint is also feminine. All these are natural

¹The Mahabharata, Adiparva, I. 102-107.

Page – 146 properties of the quick artistic temperament prone to lose balance by throwing all itself outward and therefore seldom perfectly sane and strong in all its parts. So much did these elements form the basis of Coleridge's own temperament that he could not perhaps imagine a genius in which they are wanting. Yet Wordsworth, Goethe, Dante and Sophocles show however that the very highest genius can exist without them. But none of the great poets I have named is so singularly masculine, so deficient in femineity as Vyasa, none dominates so much by intellect and personality, yet satisfies so little the romantic imagination. Indeed no poet at all near the first rank has the same granite mind in which impressions are received with difficulty but once received are ineffaceable, the same bare energy and strength without violence and the same absolute empire of inspired intellect over the more showy faculties. In his austere self-restraint and economy of power he is indifferent to ornament for its own sake, to the pleasures of poetry as distinguished from its ardours, to little graces and indulgences of style. The substance counts for everything and the form has to limit itself to its proper work of expressing with precision and power the substance. Even his most romantic pieces have a virgin coldness and loftiness in their beauty. To intellects fed on the elaborate pomp and imagery of Kalidasa's numbers and the somewhat gaudy, expensive and meretricious spirit of English poetry, Vyasa may seem bald and unattractive. To be fed on the verse of Spenser, Shelley, Keats, Byron and Tennyson is no good preparation for the severe classics. It is, indeed, I believe, the general impression of many "educated" young Indians that the Mahabharata is a mass of old wives' stories without a spark of poetry or imagination. But to those who have bathed even a little in the fountain-head of poetry, and can bear the keenness and purity of these mountain sources, the naked and unadorned poetry of Vyasa is as delightful as to bathe in a chill fountain in the heats of summer. They find that one has an unfailing source of tonic and refreshment to the soul; one comes into relation with a mind whose bare strong contact has the power of infusing strength, courage and endurance. There are certain things which have this inborn power and are accordingly valued by those who have felt deeply its properties

Page – 147 — the air of the mountains or the struggle of a capable mind with hardship and difficulty; the Vedanta philosophy, the ideal of the niskāma dharma, the poetry of Vyasa, three closely related entities are intellectual forces that exercise a similar effect and attraction. The style of this powerful writer is perhaps the one example in literature of strength in its purity, a strength undefaced by violence and excess, yet not weakened by flagging and negligence. It is less propped or helped out by any artifices and aids than any other poetic style. Vyasa takes little trouble with similes, metaphors, rhetorical turns, the usual paraphernalia of poetry, nor when he uses them, is he at pains to select such as will be new and curiously beautiful; they are there to define more clearly what he has in mind, and he makes just enough of them for that purpose, never striving to convert them into a separate grace or a decorative element. They have force and beauty in their context but cannot be turned into elegant excerpts; in themselves they are in fact little or nothing. When Bhima is spoken of as breathing hard like a weakling borne down by a load too heavy for him, there is nothing in the simile itself. It derives its force from its aptness to the heavy burden of unaccomplished revenge which the fierce spirit of the strong man was condemned to bear. We may say the same of his epithets, that great preoccupation of romantic artists; they are such as are most natural, crisp and firm, but suited to the plain idea and only unusual when the business in hand requires an unusual thought, but never recherché or existing for their own beauty. Thus when he is describing the greatness of Krishna and hinting his claims to be considered as identical with the Godhead, he gives him the one epithet aprameya, immeasurable, which is strong and unusual enough to rise to the thought, but not to be a piece of literary decoration or a violence of expression. In brief, he religiously avoids overstress, his audacities of phrase are few, and they have a grace of restraint in their boldness. There is indeed a rushing vast Valmikian style which intervenes often in the Mahabharata, but it is evidently the work of a different hand, for it belongs to a less powerful intellect, duller poetic insight and coarser taste, which has yet caught something of the surge and cry of Valmiki's oceanic poetry. Vyasa in fact stands at the opposite pole from

Page – 148 Valmiki. The poet of the Ramayana has a flexible and universal genius embracing the Titanic and the divine, the human and the gigantic at once or with an inspired ease of transition. But Vyasa is unmixed Olympian, he lives in a world of pure verse and diction, enjoying his own heaven of golden clearness. We have seen what are the main negative qualities of the style; pureness, strength, grandeur of intellect and personality are its positive virtues. It is the expression of a pregnant and forceful mind, in which the idea is sufficient to itself, conscious of its own intrinsic greatness; when this mind runs in the groove of narrative or emotion, the style wears an air of high and pellucid ease in the midst of which its strenuous compactness and brevity moves and lives as a saving and strengthening spirit; but when it begins to think rapidly and profoundly, as often happens in the great speeches, it is apt to leave the hearer behind; sufficient to itself, thinking quickly, briefly and greatly, it does not care to pause on its own ideas or explain them at length, but speaks as it thinks, in a condensed often elliptical style, preferring to indicate rather than expatiate, often passing over the steps by which it should arrive at the idea and hastening to the idea itself; often it is subtle and multiplies many shades and ramifications of thought in a short compass. From this arises that frequent knottiness and excessive compression of logical sequence, that appearance of elliptical and sometimes obscure expression, which so struck the ancient critics in Vyasa and which they expressed in the legend that when dictating the Mahabharata to Ganesha — for it was Ganesha's stipulation that not for one moment should he be left without matter to write — the poet in order not to be outstripped by his divine scribe threw in frequently knotty and close-knit passages which forced the lightning swift hand to pause and labour slowly over the work.¹ To a strenuous mind these passages are, from the exercise they give to the intellect, an added charm, just as a mountain climber takes an especial delight in steep ascents which let him feel his ability. Of one thing, however, we may be confident in reading Vyasa that the expression will always be just to the thought; he never palters with or labours to dress up the reality within him. For the rest we must

¹The Mahabharata, Adiparva, I. 78-83.

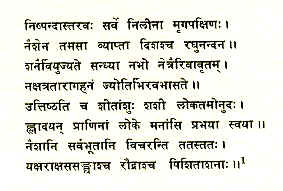

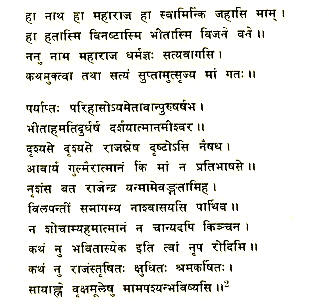

Page – 149 evidently trace this peculiarity to the compact, steep and sometimes elliptical, but always strenuous diction of the Upanishads in which the mind of the poet was trained and his personality tempered. At the same time, like the Upanishads themselves or like the enigmatic Aeschylus, he can be perfectly clear, precise and full whenever he chooses; and he more often chooses than not. His expression of thought is usually strong and abrupt, his expression of fact and of emotion strong and precise. His verse has similar peculiarities. It is a golden and equable stream that sometimes whirls itself into eddies or dashes upon rocks, but it always runs in harmony with the thought. Vyasa has not Valmiki's movement as of the sea, the wide and unbroken surge with its infinite variety of waves, which enables him not only to find in the facile anustup metre a sufficient vehicle for his vast and ambitious work but to maintain it throughout without its palling or losing its capacity of adjustment to ever-varying moods and turns of narrative. But in his narrower limits and on the level of his lower flight Vyasa has great subtlety and fineness. Especially admirable is his use, in speeches, of broken effects such as would in less skilful hands have become veritable discords; and again in narrative of the simplest and barest metrical movements, as in the opening Sarga of the Sabhaparva, to create certain calculated effects. But it would be idle to pretend for him any equality as a master of verse with Valmiki. When he has to rise from his levels to express powerful emotion, grandiose eloquence or swift and sweeping narrative, he cannot always effect it in the anustup metre; he falls back more often than not on the rolling magnificence of the tristup (and its variations) which best sets and ennobles his strong-winged austerity. Be its limits what one will, this is certain that there was never a style and verse of such bare, direct and resistless strength as this of Vyasa's or one that went so straight to the heart of all that is heroic in a man. Listen to the cry of insulted Draupadi to her husband:

¹The Mahabharata, Virataparva, 17. 15.

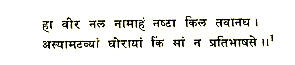

Page – 150 "Arise, arise, O Bhimasena, wherefore liest thou like one that is dead ? For nought but dead is he whose wife a sinful hand has touched and lives."

Or the reproach of Krishna to Arjuna for his weak pity which opens the second Sarga [Adhyaya] of the Bhagavadgita. Or again hear Krishna's description of Bhima's rage and solitary brooding over revenge and his taunting accusations of cowardice:

"At other times, O Bhimasena, thou praisest war, thou art all for crushing Dhritarashtra's heartless sons who take delight in death; thou sleepest not at night, O conquering soldier, but wakest lying face downwards, and ever thou utterest dread speech of storm and wrath, breathing fire in the torment of thy own rage and thy mind is without rest like a smoking fire, yea, thou liest all apart breathing heavily like a weakling borne down (distressed) by his load, so that some who know not, even think thee mad. For as an elephant tramples on uprooted trees and breaks them to fragments, so thou stormest along with labouring breath hurting earth with thy feet. Thou takest no delight in all these people but cursest them in thy heart, O Bhima, son of Pandu, nor in aught else hast thou any pleasure night or day; but thou sittest in secret like one weeping and sometimes of a sudden laughest aloud, yea, thou sittest for long with thy head between thy knees and thy eyes closed; and then again thou starest before thee frowning and clenching thy teeth, thy every action is one of wrath. 'Surely as the father Sun is seen in the East when luminously he ascendeth and surely as wide with rays he wheeleth down to his release in the West, so sure is this oath I utter and never shall be broken. With this club I will meet and slay this haughty Duryodhana,' thus touching thy club thou swearest among thy brothers. And today thou thinkest of peace, O Warrior! Ah yes, I know the hearts of those that clamour for war alter very strangely when war showeth its face, since fear findeth out even thee, O Bhima! Ah yes, son of Pritha, thou seest omens adverse both when thou sleepest and when thou wakest, therefore thou desirest peace. Ah yes, thou feelest no more the man in thyself, but an eunuch and thy heart sinketh with alarm,

Page – 151 therefore art thou thus overcome. Thy heart quakes, thy mind fainteth, thou art seized with a trembling in thy thighs, therefore thou desirest peace. Verily, O son of Pritha, wavering and inconstant is the heart of a mortal man, like the pods of the silk-cotton driven by the swiftness of every wind. This shameful thought of thine, monstrous as a human voice in a dumb beast, makes the heart of Pandu's son to sink like (ship-wrecked) men that have no raft. Look on thine own deeds, O seed of Bharata, remember thy lofty birth! Arise, put off thy weakness; be firm, O heart of a hero; unworthy of thee is this languor; what he cannot win by the mightiness of him, that a Kshatriya will not touch."¹

This passage I have quoted at some length because it is eminently characteristic of Vyasa's poetical method. Another poet would have felt himself justified by the nature of the speech in using some wild and whirling words seeking vividness by exaggeration, at the very least in raising his voice a little. Contrast with this the perfect temperance of this passage, the confident and unemotional reliance on the weight of what is said, not on the manner of saying it. The vividness of the portraiture arises from the quiet accuracy of vision and the care in the choice of simple but effective words, not from any seeking after the salient and graphic such as gives Kalidasa his wonderful power of description; and the bitterness of the taunts arises from the quiet and searching irony with which the shaft is tipped and not from any force used in driving them home. Yet every line goes straight as an arrow to its mark, every word is the utterance of a strong man speaking to a strong man and gives iron to the mind. Strength is one constant term of the Vyasic style; temperance, justness of taste is the other. Strength and a fine austerity are then the two tests which give us safe guidance through the morass of the Mahabharata; where these two exist together, we may reasonably presume some touch of Vyasa; where they do not exist or do not conjoin, we feel at once the redactor or the interpolator. I have spoken of another poet whose more turbid and vehement style breaks con-

¹The Mahabharata, Udyogaparva, 75.4 - 23.

Page – 152 tinually into the pure gold of Vyasa's work. The whole temperament of this redacting poet, for he is something more than an interpolator, has its roots in Valmiki; but like most poets of a secondary and fallible genius he exaggerates, while adopting the more audacious and therefore the more perilous tendencies of his master. The love of the wonderful touched with the grotesque, the taste for the amorphous, a marked element in Valmiki's complex temperament, is with his follower something like a malady. He grows impatient with the apparent tameness of Vyasa's inexorable self-restraint, and restlessly throws in here couplets, there whole paragraphs of a more flamboyant vigour. Occasionally this is done with real ability and success, but as a rule they are true purple patches, daubs of paint on the stainless dignity of marble. For his rage for the wonderful is not always accompanied by the prodigious sweep of imagination which in Valmiki successfully grasps and compels the most reluctant materials. The result is that puerilities and gross breaches of taste fall easily and hardily from his pen. Not one of these could we possibly imagine as consistent with the severe, self-possessed intellect of Vyasa. Fineness, justness, discrimination and propriety of taste are the very soul of the man. Nowhere is his restrained and quiet art more visible than when he handles the miraculous. But since the Mahabharata is honeycombed with the work of inept wondermongers, we are driven for an undisturbed appreciation of it to works which are not parts of the original Mahabharata and are yet by the same hand, the Nala and the Savitri. These poems have all the peculiar qualities which we have decided to be very Vyasa: the style, the diction, the personality are identical and refer us back to him as clearly as the sunlight refers us back to the sun, and yet they have something which the Mahabharata has not. Here we have the very morning of Vyasa's genius, when he was young and ardent, perhaps still under the immediate influence of Valmiki (one of the most pathetic touches in the Nala is borrowed straight out of the Ramayana), at any rate able, without ceasing to be finely restrained, to give some rein to his fancy. The Nala therefore has the delicate and unusual romantic grace of a young and severe classic who has permitted himself to go a-maying in the

Page – 153 fields of romance. There is a remote charm of restraint in the midst of abandon, of vigilance in the play of fancy which is passing sweet and strange. The Savitri is a maturer and nobler work, perfect and restrained in detail, but it has still some glow of the same youth and grace over it. This then is the rare charm of these two poems that we find there the soul of the pale and marble Rishi, the philosopher, the great statesman, the strong and stem poet of war and empire, when it was yet in its radiant morning, far from the turmoil of courts and cities and the roar of the battlefield and had not yet scaled the mountain-tops of thought. Young, a Brahmacharin and a student, Vyasa dwelt with the green silences of earth, felt the fascination and loneliness of the forests of which his earlier poetry is full, and walked by many a clear and lucid river white with the thronging water-fowl, perhaps Payoshni, that ocean-seeking stream, or heard the thunder of multitudinous crickets in some lone tremendous forest, or with Valmiki's mighty stanzas in his mind saw giant-haunted glooms, dells where faeries gathered, brakes where some Python from the underworld came out to bask or listened to the voices of Kinnaris on the mountain-tops. In such surroundings wonders might seem natural and deities as in Arcadia might peep from under every tree. Nala's messengers to Damayanti are a troop of golden-winged swans that speak with a human voice; he is intercepted on his way by gods who make him their envoy to a mortal maiden; he receives from them gifts more than human, fire and water come to him at his bidding and flowers bloom in his hands; in his downfall the dice become birds who fly away with his remaining garment; when he wishes to cut in half the robe of Damayanti, a sword comes ready to his hand in the desolate cabin; he meets the Serpent-King in the ring of fire and is turned by him into the deformed charioteer, Bahuka; the tiger in the forest turns away from Damayanti without injuring her and the lustful hunter falls consumed by the power or offended chastity. The destruction of the caravan by wild elephants, the mighty driving of Nala, the counting of the leaves or the cleaving of the Vibhitaka tree; every incident almost is full of that sense of beauty and wonder which were awakened in Vyasa by his early surroundings. We ask whether this beautiful fairy-tale is the

Page – 154 work of that stern and high poet with whom the actualities of life were everything and the flights of fancy counted for so little. Yet if we look carefully, we shall see in the Nala abundant proof of the severe touch of Vyasa, just as in his share of the Mahabharata fleeting touches of wonder and strangeness, gone as soon as glimpsed, evidence a love of the supernatural, severely bitted and reined in. Especially do we see the poet of the Mahabharata in the artistic vigilance which limits each supernatural incident to a few light strokes, to the exact place and no other where it is wanted and the exact amount and no more than is necesssary. (It is this sparing economy of touch almost unequalled in its beauty of just rejection, which makes the poem an epic instead of a fairy-tale in verse.) There is, for instance, the incident of the swans; we all know to what prolixities of pathos and bathos vernacular poets like the Gujarati Premanand have enlarged this feature of the story. But Vyasa introduced it to give a certain touch of beauty and strangeness and that touch once imparted, the swans disappear from the scene; for his fine taste felt that to prolong the incident by one touch more would have been to lower the form and run the risk of raising a smile. Similarly in the Savitri what a tremendous figure a romantic poet would have made of Death, what a passionate struggle between the human being and the master of tears and partings! But Vyasa would have none of this; he had one object, to paint the power of a woman's silent love and he rejected everything which went beyond this or which would have been merely decorative. We cannot regret his choice. There have been plenty of poets who could have given us imaginative and passionate pictures of Love struggling with Death, but there has been only one who could give us a Savitri. In another respect also the Nala helps us materially to appreciate Vyasa's genius. His dealings with Nature are a strong test of a poet's quality; but in the Mahabharata proper, of all epics the most pitilessly denuded of unnecessary ornament, natural description is rare. We must therefore again turn for aid to the poems which preceded his hard and lofty maturity. Vyasa's natural description as we find it there corresponds to the nervous, masculine and hard-strung make of his intellect. His treatment

Page – 155 is always puissant and direct without any single pervasive atmosphere except in sunlit landscapes, but always effectual, realizing the scene strongly or boldly by a few simple but sufficient words. There are some poets who are the children of Nature, whose imagination is made of her dews, whose blood thrills to her with the perfect impulse of spiritual kinship; Wordsworth is of these and Valmiki. Their voices in speaking of her unconsciously become rich and liquid and their words are touched with a subtle significance of thought or emotion. There are others who hold her with a strong sensuous grasp by virtue of a ripe, sometimes an over-ripe delight in beauty; such are Shakespeare, Keats, Kalidasa. Others again approach her with a fine or clear intellectual sense of charm as do some of the old classical poets. Hardly in the rank of poets are those who like Dryden or Pope use her, if at all, only to provide them with a smoother well-turned literary expression. Vyasa belongs to none of these, and yet often touches the first three at particular points without definitely coinciding with any. He takes the kingdom of Nature by violence. Approaching her from outside his masculine genius forces its way to her secret, insists and will take no denial. Accordingly he is impressed at first contact by the harmony in the midst of variety of her external features, absorbs these into strong retentive imagination, meditates on them and so reads his way to the closer impression, the inner sense behind that which is external, the personal temperament of a landscape. In his record of what he has seen, this impression more often than not comes first as that which abides and prevails; sometimes it is all he cares to record; but his tendency towards perfect faithfulness to the vision within leads him, when the scene is still fresh to his eye, to record the data through which the impression was reached. We have all experienced the way in which our observation of a scene, conscious or unconscious, forms itself out of various separate and often uncoordinated impressions which, if we write a description at the time or soon after and are faithful to ourselves, find their way into the picture, even at the expense of symmetry; but if we allow a long time to elapse before we recall the scene, there returns to us only a single self-consistent impression which without accurately rendering it, retains its essence and its atmosphere.

Page – 156 Something of this sort occurs in our poet; for Vyasa is always faithful to himself. When he records the data of his impression, he does it with force and clearness, frequently with a luminous atmosphere around the object, especially with a delight in the naked beauty of the single clear word which at once communicates itself to the hearer. First come the strong and magical epithets or the brief and puissant touches by which the soul of the landscape is made visible and palpable, then the enumeration sometimes only stately, at others bathed in a clear loveliness. The fine opening of the twelfth Sarga of the Nala is a signal example of this method. At the threshold we have the great and sombre line,

A void tremendous forest thundering With crickets,

striking the keynote of gloom and loneliness, then the cold stately enumeration of the forest's animal and vegetable peoples, then again the strong and revealing epithet in his "echoing woodlands sound-pervaded"; then follows "river and lake and pool and many beasts and many birds" and once more the touch of wonder and weirdness:

She many alarming shapes

making magical the bare following lines and especially the nearest,

And pools and tarns and summits everywhere,

¹The Mahabharata, Vanaparva, 64.1. ²ibid., Vanaparva, 64.7,9. ³The Mahabharata, 64.8.

Page – 157 with its poetical delight in the bare beauty of words. It is instructive to compare with this passage the wonderful silhouette of night in Valmiki's Book of the Child:

"Motionless are all trees and shrouded the beasts and birds and the quarters filled, O joy of Raghu, with the glooms of night; slowly the sky parts with evening and grows full of eyes; dense with stars and constellations it glitters with points of light; and now yonder with cold beams rises up the moon and thrusts away the shadows from the world gladdening the hearts of living things on earth with its luminousness. All creatures of the night are walking to and fro and spirit-bands and troops of giants and the carrion-feeding jackals begin to roam."

Here every detail is carefully selected to produce a certain effect, the charm and weirdness of falling night in the forest; not a word is wasted; every epithet, every verb, every image is sought out and chosen so as to aid this effect, while the vowelisation is subtly managed and assonance and the composition of sounds skilfully yet unobtrusively woven so as to create a delicate, wary and listening movement, as of one walking in the forests by moonlight and afraid that the leaves may speak under his footing or his breath grow loud enough to be heard by himself or by beings whose presence he does not see but fears. Of such delicately imaginative art as this Vyasa was not capable, he could not sufficiently turn his strength into sweetness. Neither had he that rare, salient and effective architecture of style which makes Kalidasa's

¹The Ramayana, Bala Kanda, 34. 15-18.

Page – 158

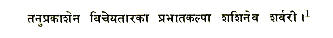

"Night on the verge of dawn with her faint gleaming moon and a few just decipherable stars."

Vyasa's art, as I have said, is singularly disinterested, niskāma; he does not write with a view to sublimity or with a view to beauty, but because he has certain ideas to impart, certain events to describe, certain characters to portray. He has an image of these in his mind and his business is to find an expression for it which will be scrupulously just to his conception. This is by no means so facile a task as the uninitiated might imagine; it is indeed considerably more difficult than to bathe the style in colour and grace and literary elegance, for it demands vigilant self-restraint, firm intellectual truthfulness and unsparing rejection, the three virtues most difficult to the gadding, inventive and self-indulgent spirit of man. The art of Vyasa is therefore a great, strenuous art; but it unfitted him, as a similar spirit unfitted the Greeks, to voice fully the outward beauty of Nature. For to delight infinitely in Nature one must be strongly possessed with the sense of colour and romantic beauty, and allow the fancy equal rights with the intellect. For all his occasional strokes of fine Nature-description he was not therefore quite at home with her. Conscious of his weakness Vyasa as he emancipated himself from Valmiki's influence ceased to attempt a kind for which his genius was not the best fitted. He is far more in his element in the expression of the feelings, of the joy and sorrow that makes this life of men; his description of emotion far excels his description of things. When he says of Damayanti:

In grief she wailed,

¹Raghuvamsha, 3.2. ²The Mahabharata, Vanaparva, 64.12.

Page – 159 the clear figure of the abandoned woman lamenting on the cliff seizes indeed the imagination, but it has a lesser inspiration than the single puissant and convincing epithet bhartrśokaparītāngī, her whole body affected with grief for her husband. Damayanti's longer laments are also of the finest sweetness and strength; there is a rushing flow of stately and sorrowful verse, the wailing of a regal grief; then as some more exquisite pain, some more piercing gust of passion traverses the heart of the mourner, golden felicities of sorrow leap out on the imagination like lightning in their swift clear greatness.

Still more strong, simple and perfect is the grief of Damayanti when she wakes to find herself alone in that desolate cabin. The restraint of phrase is perfect, the verse is clear, equable and unadorned, yet hardly has Valmiki himself written a truer utterance of emotion than this:

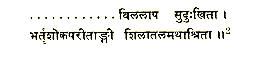

"Ah my lord! Ah my king! Ah my husband! Why hast thou forsaken me ? Alas, I am slain, I am undone, I am afraid in the lonely forest. Surely, O king, thou wert good and truthful,

¹The Mahabharata, Vanaparva, 64.19. ²The Mahabharata, Vanaparva, 63.3,4,8-12.

Page – 160 how then having sworn to me so, hast thou abandoned me in my sleep and fled ? Long enough hast thou carried this jest of thine, O lion of men, I am frightened, O unconquerable; show thyself, my lord and prince. I see thee! I see thee! Thou art seen, O lord of the Nishadas, covering thyself there with the bushes; why dost thou not speak to me? Cruel king! that thou dost not come to me thus terrified here and wailing and comfort me! It is not for myself I grieve nor for aught else; it is for thee I weep thinking what will become of thee left all alone. How wilt thou fare under some tree at evening, hungry and thirsty and weary, not beholding me, O my king?"

The whole of this passage with its first pang of terror and the exquisite anticlimax, "I am slain, I am undone, I am afraid in the desert wood", passing quietly into sorrowful reproach, the despairing and pathetic attempt to delude herself by thinking the whole a practical jest, and the final outburst of that deep maternal love which is a part of every true woman's passion, is great in its truth and simplicity. Steep and unadorned is Vyasa's style, but at times it has far more power to move and to reach the heart than mere elaborate and ambitious poetry. As Vyasa progressed in years, his personality developed towards intellectualism and his manner of expressing emotion became sensibly modified. In the Savitri he first reveals his power of imparting to the reader a sense of poignant but silent feeling, feeling in the air, unexpressed or rather expressed in action. Sometimes even in very silence; this power is a notable element in some of the great scenes of the Mahabharata: the silence of the Pandavas during the mishandling of Draupadi, the mighty silence of Krishna while the assembly of kings rages and roars around him and Shishupala again and again hurls forth on him his fury and contempt and the hearts of all men are troubled, the stern self-restraint of his brothers when Yudhishthira is smitten by Virata, are instances of the power I mean. In the Mahabharata proper we find few expressions of pure feeling, none at least which have the triumphant power of Damayanti's laments in the Nala. Vyasa had by this time taken his bent; his heart and imagination had become filled with the pomp of

Page – 161 thought and genius and the greatness of all things mighty and bold and regal; when therefore his characters feel powerful emotion, they are impelled to express it in the dialect of thought. We see the heart in their utterances but it is not the heart in its nakedness, it is not the heart of the common man; or rather it is the universal heart of man but robed in the intellectual purple. The note of Sanskrit poetry is always aristocratic; it has no answer to the democratic feeling or to the modern sentimental cult of the average man, but deals with exalted, large and aspiring natures whose pride it is that they do not act like common men (prākrto janah). They are the great spirits, the mahājanāh, in whose footsteps the world follows. Whatever sentimental objections may be urged against this high and arrogating spirit, it cannot be doubted that a literature pervaded with the soul of hero-worship and noblesse oblige and full of great examples is eminently fitted to elevate and strengthen a nation and prepare it for a great part in history. And with this high tendency of the literature there is no poet who is so deeply imbued as Vyasa. Even the least of his characters is an intellect and a personality; and of intellectual personality their every utterance reeks, as it were, and is full. I have already quoted the cry of Draupadi to Bhima; it is a supreme utterance of insulted feeling, and yet note how it expresses itself, in the language of intellect, in a thought:

The whole personality of Draupadi breaks out in that cry, her chastity, her pride, her passionate and unforgiving temper, but it flashes out not in an expression of pure feeling, but in a fiery and pregnant apophthegm. It is this temperament, this dynamic force of intellectualism blended with heroic fire and a strong personality that gives its peculiar stamp to Vyasa's writing and distinguishes it from that of all other epic poets. The heroic and profoundly intellectual rational type of the Bharata races, the Kurus, Bhojas and Panchalas who created the Veda and the Vedanta, find in Vyasa their fitting poetical type and exponent,

¹The Mahabharata, Virataparva, 17.15.

Page – 162 just as the mild and delicately moral temper of the more eastern Koshalas has realised itself in Valmiki and through the Ramayana so largely dominated Hindu character. Steeped in the heroic ideals of the Bharata, attuned to their profound and daring thought and temperament, Vyasa has made himself the poet of the high-minded Kshatriya caste, voices their resonant speech, breathes their aspiring and unconquerable spirit, mirrors their rich and varied life with a loving detail and moves through his subject with a swift yet measured movement like the march of an army towards battle. A comparison with Valmiki is instructive of the varying genius of these great masters. Both excel in epical rhetoric, if such a term as rhetoric can be applied to Vyasa's direct and severe style, but Vyasa's has the air of a more intellectual, reflective and experienced stage of poetical advance. The longer speeches in the Ramayana, those even which have most the appearance of set, argumentative oration, proceed straight from the heart, the thoughts, words, reasonings come welling up from the dominant emotion or conflicting feeling of the speaker; they palpitate and are alive with the vital force from which they have sprung. Though belonging to a more thoughtful, gentle and cultured civilisation than Homer's, they have, like his, the large utterance which is not of primitive times, but of the primal emotions. Vyasa's have a powerful but austere force of intellectuality. In expressing character they firmly expose it rather than spring half-unconsciously from it; their bold and finely planned consistency with the original conception reveals rather the conscientious painstaking of an inspired but reflective artist than the more primary and impetuous creative impulse. In their management of emotion itself a similar difference becomes prominent. Valmiki, when giving utterance to a mood or passion simple or complex, surcharges every line, every phrase, turn of words or movement of verse with it; there are no lightning flashes but a great depth of emotion swelling steadily, inexhaustibly and increasingly in a wonder of sustained feeling, like a continually rising wave with low crests of foam. Vyasa has a high level of style with a subdued emotion behind it occasionally breaking into poignant outbursts. It is by sudden beauties that

Page – 163 he rises above himself and not only exalts, stirs and delights us at his ordinary level, but memorably seizes the heart and imagination. This is the natural result of the peculiarly disinterested art which never seeks out anything striking for its own sake, but admits it only when it arises uncalled from the occasion. Vyasa is therefore less broadly human than Valmiki, he is at the same time a wider and more original thinker. His supreme intellect rises everywhere out of the mass of insipid or turbulent redaction and interpolation with bare and grandiose outlines. A wide searching mind, historian, statesman, orator, a deep and keen looker into ethics and conduct, a subtle and high-aiming politician, theologian and philosopher, it is not for nothing that Hindu imagination makes the name of Vyasa loom so large in the history of Aryan thought and attributes to him work so important and manifold. The wideness of the man's intellectual empire is evident throughout the work; we feel the presence of the great Rishi, the original thinker who has enlarged the boundaries of ethical and religious outlook. Modern India since the Musulman advent has accepted the politics of Chanakya in preference to Vyasa's. Certainly there was little in politics concealed from that great and sinister spirit. Yet Vyasa perhaps knew its subtleties quite as well, but he had to ennoble and guide him a high ethical aim and an august imperial idea. He did not, like European imperialism, unable to rise above the idea of power, accept the Jesuitic doctrine of any means to a good end, still less justify the goodness of the end by that profession of an utterly false disinterestedness which ends in the soothing belief that plunder, arson, outrage and massacre are committed for the good of the slaughtered nation. Vyasa's imperialism frankly accepts war and empire as the result of man's natural lust for power and dominion, but demands that empire should be won by noble and civilised methods, not in the spirit of the savage, and insists, once it is won, not on its powers, but on its duties. Valmiki too has included politics in his wide sweep; his picture of an ideal imperialism is sound and noble and the spirit of the Koshalan Ikshwakus that monarchy must be broad-based on the people's will and yet broader-based on justice, truth and good government, is admirably developed as an

Page – 164 undertone of the poem. But it is an undertone only, not as in the Mahabharata its uppermost and weightiest drift. Valmiki's approach to politics is imaginative, poetic, made from outside. He is attracted to it by the unlimited curiosity of an universal mind and still more by the appreciation of a great creative artist ; only therefore when it gives opportunities for a grandiose imagination or is mingled with the motives of conduct and acts on character. He is a poet who makes occasional use of public affairs as part of his wide human subject. The reverse may, with some appearance of truth, be said of Vyasa that he is interested in human action and character mainly as they move and work in relation to a large political background. From this difference in temper and mode of expression arises a difference in the mode also of portraying character. Vyasa's knowledge of character is not so intimate, emotional and sympathetic as Valmiki's; it has more of a heroic inspiration, less of a divine sympathy. He has reached it not like Valmiki immediately through the heart and imagination, but deliberately through intellect and experience, a deep criticism and reading of men; the spirit of shaping imagination has come afterwards like a sculptor using the materials labour has provided for him. It has not been a light leading him into the secret places of the heart. Nevertheless the characterisation, however reached, is admirable and firm. It is the fruit of a lifelong experience, the knowledge of a statesman who has had much to do with the ruling of men and has been himself a considerable part in some great revolution full of astonishing incidents and extraordinary characters. With that high experience his brain and his soul are full. It has cast his imagination into colossal proportions, provided him with majestic conceptions which can dispense with all but the simplest language for expression; for they are so great that the bare precise statement of what is said and done seems enough to make language epical. His character-drawing indeed is more epical, less psychological than Valmiki's. Truth of speech and action gives us the truth of nature and it is done with strong purposeful strokes that have the power to move the heart and enlarge and ennoble the imagination which is what we mean by the epic in poetry. In Valmiki there are marvellous and revealing touches

Page – 165 which show us the secret something in character usually beyond the expressive power either of speech and action; they are touches oftener found in the dramatic artist than the epic, and seldom fall within Vyasa's method. It is the difference between a strong and purposeful artistic synthesis and the beautiful, subtle and involute symmetry of an organic existence evolved and inevitable rather than shaped and purposed. His deep preoccupation with the ethical issues of speech and action is very notable. His very subject is one of practical ethics, the establishment of a Dharmarajya, an empire of the just, by which is meant no millennium of the saints, but the practical ideal of government with righteousness, purity and unselfish toil for the common good as its saving principles. It is true that Valmiki is a more humanely moral spirit than Vyasa, in as much as ordinary morality is most effective when steeped in emotion, proceeding from the heart and acting through the heart. Vyasa's ethics like everything else in him takes a double stand on intellectual scrutiny and acceptance and on personal strength of character; his characters having once adopted by intellectual choice and in harmony with their temperaments a given line of conduct, throw the whole heroic force of their nature into its pursuit. He is therefore pre-eminently a poet of action. Krishna is his authority in all matters, religious and ethical, and it is noticeable that Krishna lays far more stress on action and far less on quiescence than any other Hindu philosopher. Quiescence in God is with him as with others the ultimate goal of existence, but he insists that that quiescence must be reached through action and, so far as this life is concerned, must exist in action; quiescence of the soul from desires there must be but there should not be and cannot be quiescence of the Prakriti from action.

¹Bhagavadgita, III. 4,5,8.

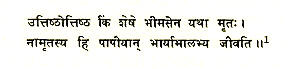

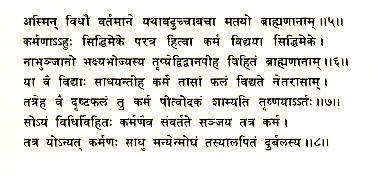

Page – 166 "Not by refraining from actions can a man enjoy actionlessness, nor by mere renunciation does he reach his soul's perfection ; but no man in the world can even for one moment remain without doing works; everyone is forced to do works, whether he wills or not, by the primal qualities born of Prakriti.... Thou do action self-controlled (or else "thou do action ever"); for action is better than inaction; if thou actest not, even the maintenance of thy body cannot be effected." Hence it follows that merely to renounce action and flee from the world to a hermitage is but vanity, and that those who rely on such a desertion of duty for attaining God lean on a broken reed. Their professed renunciation of action is only a nominal renunciation, for they merely give up one set of actions to which they are called for another to which in a great number of cases they have no call or fitness. If they have that fitness, they may certainly attain God, but even then action is better than sannyāsa. Hence the great and pregnant paradox that in action is real actionlessness, while inaction is merely another form of action itself.

"He who quells his sense-organs of action but sits remembering in his heart the objects of sense, that man of bewildered soul is termed a hypocrite." "Sannyasa (renunciation of works) and Yoga through action both lead to the highest good but of the two, Yoga through action is better than renunciation of action. Know him to be the perpetual Sannyasi who neither loathes nor longs, for he, O great-minded, being free from the dualities is easily released from the chain." "He who can see inaction in

¹Bhagavadgita, III. 6. ²ibid., V. 2. ³ibid., V. 3. 4ibid., IV. 18.

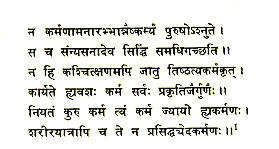

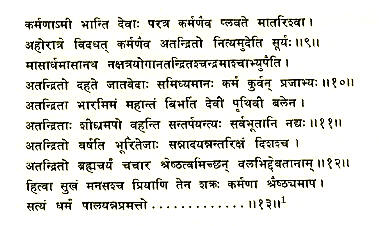

Page – 167 action and action in inaction, he is the wise among men, he does all actions with a soul in union with God." From this lofty platform the great creed rises to its crowning ideas, for since we must act, but neither for any human or future results of action nor for the sake of the action itself, and yet action must have some goal to which it is devoted, there is no goal left but God. We must then devote our actions to God and through that rise to complete surrender of the personality to him, whether in the idea of him manifest through Yoga or the idea of him unmanifest through God-Knowledge. "They who worship Me as the imperishable, illimitable, unmanifest, controlling all the organs, one-minded to all things, they doing good to all creatures attain to Me. But far greater is their pain of endeavour whose hearts cleave to the Unmanifest, for hardly can the salvation in the unmanifest be attained by men that have a body. But they who reposing all actions in Me, to Me devoted contemplate and worship Me in single-minded Yoga, speedily do I become their saviour from the gulf of death and the world, for their hearts, O Partha, have entered into Me. On Me repose thy mind, pour into Me thy reason, in Me wilt thou then have thy dwelling, doubt it not. Yet if thou canst not steadfastly repose thy mind in Me, desire, O Dhananjaya, to reach Me by Yoga through askesis. If that too thou canst not, devote thyself to actions for Me, since also by doing actions for My sake thou wilt attain to thy soul's perfection. If even for this thou art too feeble, then abiding in Yoga with Me with a soul subdued abandon utterly desire for the fruits of action. Far better than askesis is knowledge and better than knowledge is concentration and better than concentration is renunciation of the fruit of deeds, for on such renunciation followeth the soul's peace."¹ Such is the ladder which Vyasa has represented Krishna as building up to God with action for its firm and sole basis. If it is questioned whether the Bhagavadgita is the work of Vyasa (whether he be Krishna of the Island is another question to be settled on its own merits), I answer that there is nothing to disprove his authorship, while on the other hand, allowing for the exigencies of

¹Bhagavadgita, XII. 3-12.

Page – 168 philosophical exposition, the style is undoubtedly his or so closely modelled on his as to defy differentiation. Moreover, the whole piece is but the philosophical justification and logical enlargement of the gospel of action preached by Krishna in the Mahabharata proper, the undoubted work of the poet. I have here no space for anything more than a quotation. Sanjaya has come to the Pandavas from Dhritarashtra and dissuaded them from battle in a speech taught him by that wily and unwise monarch; it is skilfully aimed at the most subtle weakness of the human heart representing the abandonment of justice and their duty as a holy act of self-abnegation and its pursuit as no better than wholesale murder and parricide. It is better for the sons of Pandu to be dependents and beggars and exiles all their lives than to enjoy the earth by the slaughter of their brothers, kinsmen and spiritual guides. Contemplation is purer and nobler than action and worldly desires. Although answering firmly to the envoy, the children of Pandu are in their hearts shaken, for as Krishna afterward tells Kama, when the destruction of a nation is at hand, wrong comes to men's eyes clothed in the garb of right. Sanjaya's argument is one Christ and Buddha would have endorsed; Christ and Buddha would have laboured to confirm the Pandavas in their scruples. On Krishna rests the final word and his answer is such as to shock seriously the conventional ideas of religious teachers to which Christianity and Buddhism have accustomed us. In a long and powerful speech he deals at great length with Sanjaya's arguments. We must remember therefore that he is debating a given point and speaking to men who have not like Arjuna the adhikāra to enter into the "highest of all mysteries". We shall then realise the close identity between his teaching here and that of the Gita.

Page – 169

The drift of Vyasa's ethical speculation has always a definite and recognisable tendency; there is a basis of customary morality and there is a higher ethic of the soul which abolishes in its crowning phase the terms of virtue and sin, because to the pure all things are pure through an august and selfless disinterestedness. This ethic takes its rise naturally from the crowning height of the Vedantic philosophy, where the soul becomes conscious of its identity with God who, whether acting or actionless, is

¹The Mahabharata, Udyogaparva, 29. "With regard to the matter at present under discussion the opinions of the Brahmanas differ. One school say that it is by work that we obtain salvation and again another school say that it is by putting aside work, and through knowledge, that we attain to salvation. It has been so laid down by the superior beings that a man, even knowing all the properties of food, will not be satisfied without eating. That knowledge alone bears fruit, which does work, not others. In this world the result of action admits of ocular proof; one oppressed by thirst is satisfied by drinking water. Therefore it has been ordained by the creator that through work results, O Sanjaya, work. Therefore the opinion that anything other than work is good, is nothing but the uttering of a fool and of a weak man. Elsewhere (i.e., in the other world) the gods are resplendent through work, the wind blows through work. Causing day and night, through work, the sleepless sun rises every day. The sleepless moon, too, goes through half months and months and certain peculiar positions of the moon (through work) and the sleepless fire enkindled (by work) burns, doing good to the creatures of the Earth. The goddess Earth, sleepless, carries this great load through her strength and the sleepless rivers carry their waters with speed, satisfying the desire of all beings. The sleepless one of mighty strength (Indra) showers rain, resounding every corner and the cardinal points; and desiring kingship among the gods he practised the austerities of a Brahmacharya life, being sleepless. Giving up pleasure and the satisfaction of his desires, the position of a chief was obtained by Shakra by means of work. He strictly observed truth, virtue." The Mahabharata (English Translation) Edited by Sri Manmatha Nath Dutt.

Page – 170 untouched by either sin or virtue. But the crown of the Vedanta is only for the highest; the moral calamities that arise from the attempt of an unprepared soul to identify self with God is sufficiently indicated in the legend of Indra and Virochana. Similarly this higher ethic is for the prepared, the initiated only, because the raw and unprepared soul will seize on the non-distinction between sin and virtue without first compassing the godlike purity without which such non-distinction is neither morally admissible nor actually conceivable. From this arises the unwillingness of Hinduism, so ignorantly attributed by Europeans to priestcraft and the Brahmin, to shout out its message to the man in the street or declare its esoteric thought to the shoeblack and the kitchen-maid. The sword of knowledge is a double-edged weapon; in the hands of the hero it can save the world, but it must not be made a plaything for children. Krishna himself ordinarily insists on all men following the duties and rules of conduct to which they are born and to which the cast of their temperaments predestined them. Arjuna he advises, if incapable of rising to the higher moral altitudes, to fight in a just cause, because it is the duty of the caste, the class of souls to which he belongs. Throughout the Mahabharata he insists on this class-standpoint that every man must meet the duties to which his life calls him in a spirit of disinterestedness, — not, be it noticed, of self-abnegation, which may be as much a fanaticism and even a selfishness as the grossest egoism itself. It is because Arjuna has best fulfilled this ideal, has always lived up to the practice of his class in a spirit of disinterestedness and self-mastery that Krishna loves him above all human beings and considers him and him alone fit to receive the higher initiation.

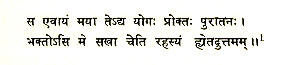

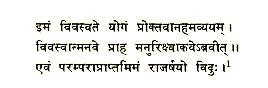

"This is the ancient Yoga which I tell thee today; because thou art My adorer and My heart's comrade; for this is the highest mystery of all."

¹Bhagavadgita, IV. 3.

Page – 171 And even the man who has risen to the heights of the initiation must cleave for the good of society to the pursuits and duties of his order; for, if he does not, the world which instinctively is swayed by the examples of its greatest will follow in his footsteps; the bonds of society will then crumble asunder and chaos come again; mankind will be baulked of its destiny. Sri Krishna illustrates this by his own example, the example of God in his manifest form.

"Looking also to the maintenance of order in the world thou shouldst act: for whatever the best practises, that other men practise; for the standard set by him is followed by the whole world. In all the Universe there is for Me no necessary action, for I have nothing I do not possess or wish to possess, and I abide always doing. For if I so abide not at all doing action vigilantly, men would altogether follow in my path, O son of Pritha; these worlds would sink if I did not actions, and I should be the author of confusion (literally, illegitimacy, the worst and primal confusion, for it disorders the family which is the fundamental unit of society) and the destroyer of the peoples. What the ignorant do, O Bharata, with their minds enslaved to the work, that the wise man should do with a free mind to maintain the order of the world; the wise man should not upset the mind of the ignorant who are slaves of their deeds, but should apply himself to all works doing customary things with a mind in Yoga."¹

It is accordingly not by airy didactic teaching so much as in the example of Krishna — and this is the true epic method — that Vyasa develops his higher ethic which is the morality of the liberated mind. But this is too wide a subject to be dealt with in the limits I have at my command. I have dwelt on Vyasa's ethical standpoint because it is of the utmost importance in the present day. Before the Bhagavadgita with its great epic commentary, the Mahabharata of Vyasa, had time deeply to influence the national mind, the heresy of Buddhism seized hold of it. Buddhism with its exaggerated emphasis on quiescence and the

¹Bhagavadgita, III. 20-26.

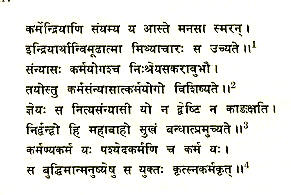

Page – 172 quiescent virtue of self-abnegation, its unwise creation of a separate class of quiescents and illuminati, its sharp distinction between monks and laymen implying the infinite inferiority of the latter, its all too facile admission of men to the higher life and its relegation of worldly action to the lowest importance possible stands at the opposite pole from the gospel of Sri Krishna and has had the very effect he deprecates; it has been the author of confusion and the destroyer of the peoples. As a result, under its influence half the nation moved in the direction of spiritual passivity and negation, the other by a natural reaction plunged deep into a splendid but enervating materialism. Our race lost three parts of its ancient heroic manhood, its grasp on the world, its magnificently ordered polity and its noble social fabric. It is by clinging to a few spars from the wreck that we have managed to perpetuate our existence and this we owe to the overthrow of Buddhism by Shankaracharya. But Hinduism has never been able to shake off the deep impress of the religion it vanquished; and therefore though it has managed to survive, it has not succeeded in recovering its old vitalising force. The practical disappearance of the Kshatriya caste (for those who now claim that origin seem to be, with a few exceptions, Vratya Kshatriyas, Kshatriyas who have fallen from the pure practice and complete temperament of their caste) has operated in the same direction. The Kshatriyas were the proper depositaries of the gospel of action; Sri Krishna himself declares:

"This imperishable Yoga I revealed to Vivaswan, Vivaswan declared it to Manu, Manu told it to Ikshwaku; thus did the royal sages learn this as a hereditary knowledge."

And when in the immense lapse of time it was lost, Sri Krishna again declared it to a Kshatriya. But when the Kshatriyas disappeared or became degraded, the Brahmins remained

¹Bhagavadgita, IV. 1,2.

Page – 173 the sole interpreters of the Bhagavadgita, and, they, being the highest caste or temperament and their thoughts therefore naturally turned to knowledge and the final end of being, bearing moreover still the stamp of Buddhism in their minds, dwelt mainly on that in the Gita which deals with the element of quiescence. They have laid stress on the goal, but they have not echoed Sri Krishna's emphasis on the necessity of action as the one sure road to the goal. Time, however, in its revolution is turning back on itself and there are signs that if Hinduism is to last and we are not to plunge into the vortex of scientific atheism and the breakdown of moral ideals which is engulfing Europe, it must survive as the religion of Vyasa for which Vedanta, Sankhya and Yoga combined to lay the foundations, which Sri Krishna announced and which Vyasa formulated. But Vyasa has not only a high political and religious thought and deep-seeing ethical judgments, he deals not only with the massive aspects and world-wide issues of human conduct, but has a keen eye for the details of government and society, the ceremonies, forms and usages, the religious and social order on the due stability of which public welfare is grounded. The principles of good government and the motives and impulses that move men to public action, no less than the rise and fall of States and the clash of mighty personalities and great powers form, incidentally and epically treated, the staple of Vyasa's epic. The poem was therefore, first and foremost, like the Iliad and Aeneid and even more than the Iliad and Aeneid, national — a poem in which the religious, social and personal temperament and ideals of the Aryan nation have found a high expression and the institutions, actions and heroes in the most critical period of its history received the judgments and criticisms of one of its greatest and soundest minds. If this had not been so we should not have had the Mahabharata in its present form. Valmiki had also dealt with a great historical period in a yet more universal spirit and with finer richness of detail, but he approached it in a poetic and dramatic manner, he created rather than criticised; while Vyasa in his manner was the critic far more than the creator. Hence later poets found it easier and more congenial to introduce their criticisms of life and thought into the Mahabharata than

Page – 174 into the Ramayana. Vyasa's poem has been increased to three-fold its original size; the additions to Valmiki, few in themselves if we set apart the Uttara Kanda, have been immaterial and for the most part of an accidental nature. Gifted with such poetical powers, limited by such intellectual and emotional characteristics, endowed with such grandeur of soul and severe purity of taste, what was the special work which Vyasa did for his country and in what, beyond the ordinary elements of poetical treatise, lies his claim to world-wide acceptance ? It has been suggested already that the Mahabharata is the great national poem of India. It is true the Ramayana also represents an Aryan civilisation idealised: Rama and Sita are more intimately characteristic types of the Hindu temperament as it finally shaped itself than are Arjuna and Draupadi; Sri Krishna, though his character is founded in the national type, yet rises far above it. But although Valmiki, writing the poem of mankind, drew his chief figures in the Hindu model and Vyasa, writing a great national epic, lifted his divine hero above the basis of national character into an universal humanity, yet the original purpose of either poem remains intact. In the Ramayana under the disguise of an Aryan golden age, the wide world with all its elemental impulses and affections finds itself mirrored. The Mahabharata reflects rather a great Aryan civilisation with the types, ideas, aims and passions of a heroic and pregnant period in the history of a high-hearted and deep-thoughted nation. It has, moreover, as I have attempted to indicate, a formative ethical and religious spirit which is absolutely corrective to the faults that have most marred in the past and mar to the present day the Hindu character and type of thought. And it provides us with this corrective not in the form of an alien civilisation difficult to assimilate and associated with other elements as dangerous to us as this is salutary, but in a great creative work of our own literature written by the mightiest of our sages (munīnāmapyaham vyāsah, Krishna has said), one therefore who speaks our own language, thinks our own thoughts and has the same national cast of mind, nature and conscience. His ideals will therefore be a corrective not only to our own faults but to the dangers of that attractive but unwholesome Asura civilisation which has

Page – 175 invaded us, especially its morbid animalism and its neurotic tendency to abandon itself to its own desires. But this does not say all. Vyasa too, beyond the essential universality of all great poets, has his peculiar appeal to humanity in general making his poem of world-wide as well as national importance. By comparing him once again with Valmiki we shall realize more precisely in what this appeal consists. The Titanic impulse was strong in Valmiki. The very dimensions of his poetical canvas, the audacity and occasional recklessness of his conceptions, the gust with which he fills in the gigantic outlines of his Ravana are the essence of Titanism; his genius was so universal and Protean that no single element of it can be said to predominate, yet this tendency towards the enormous enters perhaps as largely into it as any other. But to the temperament of Vyasa the Titanic was alien. It is true he carves his figures so largely (for he was a sculptor in creation rather than a painter like Valmiki) that looked at separately they seem to have colossal stature, but he is always at pains so to harmonise them that they shall appear measurable to us and strongly human. They are largely and boldly human, oppressive and sublime, but never Titanic. He loves the earth and the heavens but he visits not Patala nor the stupendous regions of Vrishaparvan. His Rakshasas, supposing them to be his at all, are epic giants or matter-of-fact ogres, but they do not exhale the breath of midnight and terror like Valmiki's demons nor the spirit of world-shaking anarchy like Valmiki's giants. This poet could never have conceived Ravana. He had neither unconscious sympathy nor a sufficient force of abhorrence to inspire him. The passions of Duryodhana though presented with great force of antipathetic insight are human and limited. The Titanic was so foreign to Vyasa's habit of mind that he could not grasp it sufficiently either to love or hate. His humanism shuts to him the outermost gates of that sublime and menacing region; he has not the secret of the storm nor has his soul ridden upon the whirlwind. For his particular work this was a real advantage. Valmiki has drawn for us both the divine and anarchic in extraordinary proportions; an Akbar or a Napoleon might find his spiritual kindred in Rama or Ravana, but with more ordinary beings such figures impress the

Page – 176 sense of the sublime principally and do not dwell with them as daily acquaintances. It was left for Vyasa to create epically the human divine and the human anarchic so as to bring idealisms of the conflicting moral types into line with the daily emotions and imaginations of men. The sharp distinction between Deva and Asura is one of the three distinct and peculiar contributions to ethical thought which India has to offer. The legend of Indra and Virochana is one of its fundamental legends. Both of them came to Brihaspati to know from him of God; he told them to go home and look in the mirror. Virochana saw himself there and concluding that he was God, asked no farther; he gave full rein to the sense of individuality in himself which he mistook for the deity. But Indra was not satisfied; feeling that there must be some mistake he returned to Brihaspati and received from him the true God-Knowledge which taught him that he was God only because all things were God, since nothing existed but the One. If he was the one God, so was his enemy, the very feelings of separateness and enmity were not permanent reality but transient phenomena. The Asura therefore is he who is profoundly conscious of his own separate individuality and yet would impose it on the world as the sole individuality; he is thus blown along on the hurricane of his desires and ambitions until he stumbles and is broken, in the great phrase of Aeschylus, against the throne of Eternal Law. The Deva, on the contrary, stands firm in the luminous heaven of self-knowledge, his actions flow not inward towards himself but outwards toward the world. The distinction that Indra draws is not between altruism and egoism but between disinterestedness and desire. The altruist is profoundly conscious of himself and he is really ministering to himself even in his altruism; hence the hot and sickly odour of sentimentalism and the taint of the Pharisee which clings about European altruism. With the perfect Hindu the feeling of self has been merged in the sense of the universe; he does his duty equally whether it happens to promote the interests of others or his own; if his action seems oftener altruistic than egoistic it is because our duty oftener coincides with the interests of others — than with our own. Rama's duty as a son calls him to sacrifice himself, to leave the empire of the world and become a beggar