|

The Problem of the Mahabharata THE POLITICAL STORY

IT WAS hinted in a recent article of the Indian Review, an unusually able and searching paper on the date of the Mahabharata war, that a society is about to be formed for discovering the genuine and original portions of our great epic. This is glad tidings to all admirers of Sanskrit literature and to all lovers of their country. For the solution of the Mahabharata problem is essential to many things, to any history worth having of Aryan civilisation and literature, to a proper appreciation of Vyasa's poetical genius and, far more important than either, to a definite understanding of the great ethical gospel which Sri Krishna came down on earth to teach as a guide to mankind in the dark Kali Yuga then approaching. But I fear that if the inquiry is to be pursued on the lines the writer of this article seemed to hint, if the Society is to rake out 8000 lines from the War Parvas and dub the result the Mahabharata of Vyasa, then the last state of the problem will be worse than its first. It is only by a patient scrutiny and weighing of the whole poem, disinterestedly, candidly and without pre-conceived notions, a consideration canto by canto, paragraph by paragraph, couplet by couplet, that we can arrive at anything solid or permanent. But this implies a vast and heart-breaking labour. Certainly, labour however vast ought not to have any terrors for a scholar, still less for a Hindu scholar; yet, before one engages in it, one requires to be assured that the game is worth the candle. For that assurance there are three necessary requisites, the possession of certain sound and always applicable tests to detect later from earlier work, a reasonable chance that such tests if applied will restore the real epic roughly if not exactly in its original form and an assurance that the epic when recovered will repay from literary, historical or other points of view the labour that has been bestowed on it. I believe that these three requisites are present in this case and shall attempt to adduce

Page – 179 a few reasons for my belief. I shall try to show that besides other internal evidence on which I do not propose just now to enter, there are certain traits of poetical style, personality and thought which belong to the original work and are possessed by no other writer. I shall also try to show that these traits may be used as a safe guide through the huge morass of verse. In passing I shall have occasion to make clear certain claims the epic thus disengaged will possess to the highest literary, historical and practical value. It is certainly not creditable to European scholarship that after so many decades of Sanskrit research, the problem of the Mahabharata which should really be the pivot for all the rest has remained practically untouched. For it is no exaggeration to say that European scholarship has shed no light whatever on the Mahabharata beyond the bare fact that it is the work of more than one hand. All else it has advanced, and fortunately it has advanced little, has been rash, arbitrary or prejudiced; theories, theories and always theories without any honestly industrious consideration of the problem. The earliest method adopted was to argue from European analogies, a method pregnant of error and delusion. If we consider the hypothesis of a rude ballad-epic doctored by "those Brahmins" — anyone who is curious on the matter may study with both profit and amusement Fraser's History of Indian Literature — we shall perceive how this method has been worked. A fancy was started in Germany...as a moral certainty. But it is not from European scholars that we must expect a solution of the Mahabharata problem. They have no qualifications for the task except a power of indefatigable research and collocation; and in dealing with the Mahabharata even this power seems to have deserted them. It is from Hindu scholarship renovated and instructed by contact with European that the attempt must come. Indian scholars have shown a power of detachment and disinterestedness and a willingness to give up cherished notions under pressure of evidence which are not common in Europe. They are not, as a rule, prone to the Teutonic sin of forming a theory in accordance with their prejudices and then finding facts or manufacturing inferences to support it.

Page – 180 When, therefore, they form a theory on their own account, it has usually some clear justification and sometimes an overwhelming array of facts and solid arguments behind it. The German scholarship possesses infinite capacity of acuteness, labour, marred by an impossible and fantastic imagination, the French of inference marred by insufficient command of facts, while in soundness of judgment Indian sane scholarship has both. It should stand first, for it must naturally move with a far greater familiarity and grasp in the sphere of Sanskrit studies than any foreign mind however able and industrious. But above all it must clearly have one advantage, an intimate feeling of the language, a sensitiveness to shades of style and expression and an instinctive feeling of what is or is not possible, which the European cannot hope to possess unless he sacrifices his sense of racial superiority and lives in some great centre like Benares as a Pundit among Pundits. I admit that even among Indians this advantage must vary with the amount of education and natural fineness of taste; but where other things are equal, they must possess it in an immeasurably greater degree than an European of similar information and critical power. For to the European Sanskrit words are no more than dead counters which he can play with and throw as he likes into places the most unnatural or combinations the most monstrous; to the Hindu they are living things the very soul of whose temperament he understands and whose possibilities he can judge to a hair. That with these advantages Indian scholars have not been able to form themselves into a great and independent school of learning is due to two causes, the miserable scantiness of the mastery in Sanskrit provided by our universities, crippling to all but born scholars, and their lack of a sturdy independence which makes us over-ready to defer to European authority. These, however, are difficulties easily surmountable. In solving the Mahabharata problem this intimate feeling for language is of primary importance; for style and poetical personality must be not indeed the only but the ultimate test of the genuineness of any given passage in the poem. If we rely upon any other internal evidence, we shall find ourselves irresistibly tempted to form a theory and square facts to it. The late Rai Bahadur Bankim Chandra Chatterji, a genius of whom

Page – 181 modern India has not produced the parallel, was a man of ripe scholarship, literary powers of the very first order and a strong critical sagacity. In his Life of Krishna (Krishnacharitra) he deals incidentally with the Mahabharata problem, he perceived clearly enough that there were different recognizable styles in the poem and he divided it into three layers, the original epic by a very great poet, a redaction of the original epic by a poet not quite so great and a mass of additions by very inferior hands. But being concerned with the Mahabharata only so far as it covered the Life of Krishna, he did not follow up this line of scrutiny and relied rather on internal evidence of a quite different kind. He saw that in certain parts of the poem Krishna's godhead is either not presupposed at all or only slightly affirmed, while in others it is the main objective of the writer; certain parts again give us a plain, unvarnished and straightforward biography and history, others are a mass of wonders and legends, often irrelevant extravagances; in some parts also the conception of the chief characters is radically departed from and defaced. He therefore took these differences as his standard and accepted only those parts as genuine which gave a plain and consistent account of Krishna the man and of others in their relation to him. Though his conclusions are to a great extent justifiable, his a priori method led him to exaggerate them, to enforce them too rigidly without the proper flexibility and scrupulous hesitation and to resort occasionally to special pleading. His book is illuminating and full of insight, and the chief contentions will, I believe, stand permanently; but some parts of his argument are exaggerated and misleading and others, which are in the main correct, are yet insufficiently supported by reasoning. It is the failure to refer everything to the ultimate test of style that is responsible for these imperfections. Undoubtedly inconsistencies of detail and treatment are of immense importance. If we find gross inconsistencies of character, if a man is represented in one place as stainlessly just, unselfish and truthful and in another as a base and selfish liar or a brave man suddenly becomes guilty of incomprehensible cowardice, we are justified in supposing two hands at work; otherwise we must either adduce very strong poetic and psychological justification for the lapse or else suppose that the poet

Page – 182 was incompetent to create or portray consistent and living characters. But if we find that one set of passages belongs to the distinct and unmistakable style of a poet who has shown himself capable of portraying great epic types, we shall be logically debarred from the saving clause. And if the other set of passages shows not only a separate style, but quite another spirit and the stamp of another personality, our assurance will be made doubly sure. Further, if there are serious inconsistencies of fact, if for instance Krishna says in one place that he can only do his best as a man and can use no divine power in human affairs, and in another foolishly uses his divine power where it is quite uncalled for, or if a considerable hero is killed three or four times over, yet always pops up again with really commendable vitality without warning or explanation until some considerate person gives him his coup de grâce, or if totally incompatible statements are made about the same person or the same event, we may find in either or all of these inconsistencies sufficient ground to assume diversity of authorship. Still even here we must ultimately refer to the style as corroborative evidence; and when the inconsistencies are grave enough to raise suspicion, but not so totally incompatible as to be conclusive, difference of style will at once turn the suspicion into certainty, while similarity may induce us to suspend judgment. And where there is no inconsistency of fact or conception and yet the difference in expression and treatment is marked, the question of style and personality becomes all-important. Now in the Mahabharata we are struck at first by the presence of two glaringly distinct and incompatible styles. There is a mass of writing in which the verse and language is unusually bare, simple and great, full of firm and knotted thinking and a high and heroic personality, the imagination strong and pure, never florid or richly coloured, the ideas austere, original and noble. There is another body of work sometimes massed together but far oftener interspersed in the other, which has exactly opposite qualities, it is Ramayanistic, rushing in movement, full and even overabundant in diction, flowing but not strict in thought, the imagination bold and vast, but often garish and highly-coloured, the ideas ingenious and poetical, sometimes of astonishing subtlety, but at others common and trailing, the

Page – 183 personality much more relaxed, much less heroic, noble and severe. When we look closer we find that the Ramayanistic part may possibly be separated into two parts, one of which has less inspiration and is more deeply imbued with the letter of the Ramayana, but less with its spirit. The first portion again has a certain element often in close contact with it which differs from it in a weaker inspiration, in being a body without the informing spirit of high poetry. It attempts to follow its manner and spirit but fails and reads therefore like imitation of a great poet. We have to ask ourselves whether this is the work of an imitator or of the original poet in his uninspired moments. Are there besides the mass of inferior or obviously interpolated work which can be easily swept aside, three distinct recognizable styles or four or only two ? In the ultimate decision of this question inconsistencies of detail and treatment will be of great consequence. But in the meantime I find nothing to prevent me from considering the work of the first poet, undoubtedly the greatest of the four, if four there are, as the original epic. It may indeed be objected that style is no safe test, for it is one which depends upon the personal preferences and ability of the critic. In an English literary periodical it was recently observed that a certain Oxford professor who had studied Stevenson like a classic attempted to apportion to Stevenson and Lloyd Osbourne their respective work in the Wrecker, but his apportionment turned out to be hopelessly erroneous. To this the obvious answer is that the Wrecker is a prose work and not poetry. There was no prose style ever written that a skilful hand could not reproduce as accurately as a practised forger reproduces a signature. But poetry, at any rate original poetry of the first class, is a different matter. The personality and style of a true poet are unmistakable to a competent mind, for though imitation, echo, adaptation or parody is certainly possible, it would be as easy to reproduce the personal note in the style as for the painter to put into his portrait the living soul of its original. The successful discrimination between original and copy depends then upon the competence of the critic, his fineness of literary feeling, his sensitiveness to style. On such points the dictum of a foreign critic is seldom of any value. One would not ask a mere

Page – 184 labourer to pronounce on the soundness of a great engineering work, but still less would one ask a mathematician unacquainted with mechanics. To minds well-equipped for the task there ought to be no insuperable difficulty in disengaging the style of a marked poetic personality from a mass of totally different work. The verdict of great art-critics on the genuineness of a professed Old Master may not be infallible, but if formed on a patient study of the technique and spirit of the work, it has at least considerable chances of being correct. But the technique and spirit of poetry are far less easy to catch by an imitator than those of great painting, the charm of words being more elusive and unanalysable than that of line and colour. In unravelling the Mahabharata especially, the peculiar inimitable nature of the style of Vyasa immensely lightens the difficulties of criticism. Had his been poetry of which the predominant grace was mannerism, it would have been imitable with some closeness; or even had it been a rich and salient style like Shakespeare's, Kalidasa's or Valmiki's, certain externals of it might have been reproduced by a skilled hand and the task of discernment rendered highly delicate and perilous. Yet even in such styles to the finest minds the presence or absence of an unanalysable personality within the manner of expression would be always perceptible. The second layer of the Mahabharata is distinctly Ramayanistic in style, yet it would be a gross criticism that could confuse it with Valmiki's own work; the difference, as is always the case in imitations of great poetry, is as palpable as the similarity. Some familiar examples may be taken from English literature. Crude as is the composition and treatment of the three parts of King Henry VI, its style unformed and everywhere full of echoes, yet when we get such lines as

Thrice is he arm'd that hath his quarrel just, And he but naked, though lock'd up in steel, Whose conscience with injustice is corrupted,

we cannot but feel that we are listening to the same poetic voice as in Richard III.

Page – 185 Shadows tonight Have struck more terror to the soul of Richard Than can the substance of ten thousand soldiers. Armèd in proof and led by shallow Richmond,

or in Julius Caesar,

The evil that men do lives after them; The good is oft interrèd with their bones,

or in the much later and richer vein of Antony and Cleopatra,

I am dying, Egypt, dying; only I here importune death awhile, until Of many thousand kisses the poor last I lay upon thy lips.

I have purposely selected passages of perfect simplicity and straightforwardness, because they appear to be the most imitable part of Shakespeare's work and are really the least imitable. Always one hears the same voice, the same personal note of style sounding through these very various passages, and one feels that there is in all the intimate and unmistakable personality of Shakespeare. We turn next and take two passages from Marlowe, a poet whose influence counted for much in the making of Shakespeare, one from Faustus,

Was this the face that launched a thousand ships And burnt the topless towers of Ilium ?

and another from Edward II,

I am that cedar, shake me not too much, And you the eagles, soar ye ne'er so high, I have the jesses that will pull you down And Aeque tandem shall that canker cry Unto the proudest peer in Brittanny.

Page – 186 The choice of words, the texture of style has a certain similarity, the run of the sentences differs little if at all; but what fine literary sense does not feel that here is another poetical atmosphere and the ring of a different voice? And yet to put a precise name on the difference would not be easy. The personal difference becomes still more marked if we take a passage from Milton in which the nameable merits are precisely the same, a simplicity in strength of diction, thought and the run of the verse,

What though the field be lost....

And when we pass farther down in the stream of literature and read

Thy thunder, conscious of the new command...

we feel that the poet has nourished his genius on the greatness of Milton till his own soft and luxurious style rises into epic vigour; yet we feel too that the lines are only Miltonic, they are not Milton. Now there are certain great poetical styles which are of a kind apart, they are so extraordinarily bare and restrained that the untutored mind often wonders what difficulty there can be in writing poetry like that; yet when the attempt is made, it is found that so far as manner goes it is easier to write somewhat like Shakespeare or Homer or Valmiki than to write like these. Just because the style is so bare, has no seizable mannerism, no striking and imitable peculiarities, the failure of the imitation appears complete and unsoftened; for in such poets there is but one thing to be caught, the unanalysable note, the personal greatness like everything that comes straight from God which 'it is impossible to locate or limit, and precisely the one that most eludes the grasp. This poetry it is always possible to distinguish with some approach to certainty from imitative or spurious work. Very fortunately the style of Vyasa is exactly such a manner of poetry. Granted therefore adhikāra in the critic, that is to say, a natural gift of fine literary sensitiveness and the careful cultivation of

Page – 187 that gift until it has become as sure a lactometer as the palate of the swan which rejects the water mingled with milk and takes the milk alone, we have in the peculiar characteristics of this poetry a test of unquestionable soundness and efficacy. But there is another objection of yet more weight and requiring as full an answer. This method of argument from style seems after all as a priori and Teutonic as any other; for there is no logical reason why the mass of writing in this peculiar style should be judged to be the original epic and not any of the three others or even part of that inferior work which was brushed aside so contemptuously. The original Mahabharata need not have been a great poem at all; it was more probably an early, rude and uncouth performance. Certain considerations however may lead us to consider our choice less arbitrary than it seems. That the War Parvas contain much of the original epic may be conceded to Professor Weber; the war is the consummation of the story and without a war there could be no Mahabharata. But the war of the Mahabharata was not a petty contest between obscure barons or a brief episode in a much larger struggle or a romantic and chivalrous emprise for the rescue of a ravished or errant beauty. It was a great political catastrophe employing the clash of a hundred nations and far-reaching political consequences; the Hindus have always considered it as the turning-point in the history of their civilisation and the beginning of a new age, and it was long used as a historical standpoint and a date to reckon from in chronology. Such an event must have had the most considerable political causes and been caused by the collision of the most powerful personalities and the most important interests. If we find no record of or allusion to these in the poem, we shall be compelled to suppose that the poet, living long after the event, regarded the war as a legend or romance which would form excellent matter for an epic and treated it accordingly. But if we find a simple and unvarnished, though not necessarily connected and consecutive account of the political conditions which preceded the war and of the men who made it and their motives, we may safely say that this also is an essential part of the epic. The Iliad deals only with an episode of the legendary siege of Troy, it covers an action of about eight days in a

Page – 188 conflict lasting ten years; and its subject is not the Trojan War but the Wrath of Achilles. Homer was under no obligation therefore to deal with the political causes that led to hostilities, even supposing he knew them. The Mahabharata stands on an entirely different footing. The war there is related from beginning to end consecutively and without break, yet it is nowhere regarded as of importance sufficient to itself but depends for its interest on causes which led up to it and the characters and clashing interests it involved. The preceding events are therefore of essential importance to the epic. Without the war, no Mahabharata, is true of this epic; but without the causes of the war, no war, is equally true. And it must be remembered that the Hindu narrative poets had no artistic predilections like that of the Greeks for beginning a story in the middle. On the contrary they always preferred to begin at the beginning. We therefore naturally expect to find the preceding political conditions and the immediate causes of the war related in the earlier part of the epic and this is precisely what we do find. Ancient India as we know was a sort of continent, made up of many great and civilised nations who were united very much like the nations of modern Europe by an essential similarity of religion and culture rising above and beyond their marked racial peculiarities; like the nations of Europe also they were continually going to war with each other, and yet had relations of occasional struggle, of action and reaction, with the other peoples of Asia whom they regarded as barbarous races outside the pale of the Aryan civilisation. Like the continent of Europe, the ancient continent of India was subject to two opposing forces, one centripetal which was continually causing attempts at universal empire, another centrifugal which was continually impelling the empires once formed to break up again into their constituent parts; but both these forces were much stronger in their action than they have usually been in Europe. The Aryan nations may be divided into three distinct groups, the Eastern of whom the Koshalas, Magadhas, Chedis, Videhas and Haihayas were the chief, the central among whom the Kurus, Panchalas and Bhojas were the most considerable; and the Western and Southern of whom there were many, small and rude yet warlike

Page – 189 and famous peoples; among those there have been none that ever became of the first importance. Five distinct times had these great congeries of nations been welded into Empire, twice by the Ikshwakus under Mandhata, son of Yuvanashwa and King Marutta, afterwards by the Haihaya Arjuna Kartavirya, again by the Ikshwaku Bhagiratha and finally by the Kuru Bharata. That the first Kuru empire was the latest is evident not only from the Kurus being the strongest nation of their time, but from the significant fact that the Koshalas by this time had faded into utter and irretrievable insignificance. The rule of the Haihayas had resulted in one of the great catastrophes of early Hindu civilisation belonging to the Eastern section of the continent which was always apt to break away from the strict letter of Aryanism. They had brought themselves by their pride and violence into collision with the Brahmin with the result of a civil war in which their empire was broken for ever by Parashurama, son of Jamadagni, and the chivalry of India massacred and for the time broken. The fall of the Haihayas left the Ikshwakus and the Bharata or the Ilian dynasty of the Kurus the two chief powers of the continent. Then seems to have followed the golden age of the Ikshwakus under the beneficent empire of Bhagiratha and his descendants as far down at least as Rama. Afterwards the Koshalas, having reached their highest point, must have fallen into that state of senile decay which, once it overtakes a nation, is fatal and irremediable. They were followed by the empire of the Bharatas. By the time of Shantanu, Vichitravirya and Pandu this empire had long been dissolved by the centrifugal force of Aryan politics into its constituent parts, yet the Kurus were among the first of the nations and the Bharata Kings of the Kurus were still looked up to as the head of civilisation. But by the time of Dhritarashtra the centripetal force had again asserted itself and the idea of another great empire loomed before the imaginations of all men. A number of nations had risen to the greatest military prestige and political force, the Panchalas under Drupada and his sons, the Kurus under Bhishmuc and his brother Acrity who is described as equalling Parashurama in military skill and courage, the Chedis under the hero and great captain Shishupala, the Magadhas built into a strong nation by Brihadratha,

Page – 190 even distant Bengal under the Poundrian Vasudeva and distant Sindhu under Vriddha Kshatra and his son Jayadratha began to mean something in the reckoning of forces. The Yadava nations counted as a great military force in the balance of politics owing to their abundant heroism and genius, but seemed to have lacked sufficient cohesion and unity to nurse independent hopes. Strong, however, as these nations were none seemed able to dispute the prize of the coming empire with the Kurus, until under Jarasandha the Barhadratha Magadha for a moment disturbed the political balance. The history of the first great Magadhan hope of empire and its extinction — not to be revived again until the final downfall of the Kurus — is told very briefly in the Sabhaparva of the Mahabharata. The removal of Jarasandha restored the original state of politics and it was no longer doubtful that to the Kurus alone could fall the future empire. But contest arose between the elder and the younger branches of the Bharata house. The question being then narrowed to a personal issue, it was inevitable that it should become largely a history of personal strife and discord; other and larger issues were involved in the dispute between the Kaurava cousins, but whatever interests, incompatibilities of temperament and difference of opinion may divide brothers, they do not engage in fratricidal conflict until they are driven to it by a long record of collision and jealousy, ever deepening personal hatred and the worst personal injuries. We see therefore that not only the early discords, the slaying of Jarasandha and the Rajasuya sacrifice are necessary to the epic but the great gambling and the mishandling of Draupadi. It cannot, however, have been personal questions alone that affected the choice of the different nations between Duryodhana and Yudhishthira; personal relations like the matrimonial connections of Dhritarashtra's family with the Sindhus and Gandharas and of the Pandavas with the Matsyas, Panchalas and Yadavas doubtless counted for much, but there must have been something more; personal enmities counted for something as in the feud cherished by the Trigartas against Arjuna. The Madras disregarded matrimonial ties when they sided with Duryodhana; the Magadhas and Chedis put aside the memory of personal wrong when they

Page – 191 espoused the cause of Yudhishthira. I believe the explanation we must gather from the hints of the Mahabharata is this, that the nations were divided into three classes, those who desired autonomy, those who desired to break the power of the Kurus and assert their own supremacy and those who imbued with old imperialistic notions desired an united India. The first followed Duryodhana because the empire of Duryodhana could not be more than the empire of a day while that of Yudhishthira had every possibility of permanence; even Queen Gandhari, Duryodhana's own mother, was able to hit this weak point in her son's ambition. The Rajasuya sacrifice had also undoubtedly identified Yudhishthira in men's minds with the imperialistic impulse of the times. We are given some important hints in the Udyogaparva. When Vidura remonstrates with Krishna for coming to Hastinapur, he tells him it was highly imprudent for him to venture there knowing as he did that the city was full of kings all burning with enmity against him for having deprived them once of their greatness, driving, by the fear of him, to take refuge with Duryodhana and eager to war against the Pandavas. This can have no intelligible reference except to the Rajasuya sacrifice. Although it was the armies of Yudhishthira that had traversed India then on their mission of conquest, Krishna was generally recognised as the great moving and master mind whose hands of execution the Pandavas were and without whom they would have been nothing. His personality dominated men's imaginations for adoration or for hatred; for that many abhorred him as an astute and unscrupulous revolutionist in morals, politics and religion, we very clearly perceive. We have not only the fiery invectives of Shishupala but the reproach of Bhurihshravas the Valhika, a man of high reputation and universally respected. Krishna himself is perfectly conscious of this; he tells Vidura that he must make efforts towards peace both to deliver his soul and to justify himself in the eyes of men. The belief that Krishna's policy and statesmanship was the really effective force behind Yudhishthira's greatness, pervades the epic. But who were these nations that resented so strongly the attempt of Yudhishthira and Krishna to impose an empire on them? It is a significant fact that the Southern and Western peoples went almost solid for

Page – 192 Duryodhana in this quarrel — Madra, the Deccan, Avanti, Sindhu Sauvira, Gandhara in one long line from Southern Mysore to Northern Kandahar; the Aryan colonies in the yet half-civilised regions of the Lower valley of the Ganges espoused the same cause. The Eastern nations, heirs of the Ikshwaku imperial idea, went equally solid for Yudhishthira. The Central peoples, repositories of the great Kuru Panchala tradition as well as the Yadavas, who were really a Central nation though they had trekked to the West, were divided. Now this distribution is exactly what we should have expected. The nations which are most averse to enter into an imperial system and cherish most their separate existence are those which are outside the centre of civilisation, hardy, warlike, only partially refined; and their aversion is still more emphatic when they have never or only for a short time been part of an empire. This is the real secret of the invincible resistance which England has opposed to all Continental schemes of empire from Philip II to Napoleon; it is the secret of her fear of Russia; it is the reason of the singular fact that only now after many centuries of great national existence has she become imbued with the imperial idea on her own account. The savage attachment to their independence of small nations like the Dutch, the Swiss, the Boers is traceable to the same cause; the fierce resistance opposed by the greater part of Spain to Napoleon was that of a nation, which once imperial and central, has fallen out of the main flood of civilisation and is therefore become provincial and attached to its own isolation. That the nations of the East and South and the Aryan colonies in Bengal should oppose the imperialist policy of Krishna and throw in their lot with Duryodhana is therefore no more than we should expect. On the other hand, nations at the very heart of civilisation, who have formed at one time or another dominant parts of an empire fall easily into imperial schemes, but personal rivalry, the desire of each to be the centre of empire, divides them and brings them into conflict, not any difference of political temperament. For nations have very tenacious memories and are always attempting to renew the great ages of their past. In the Eastern peoples the imperialistic idea was very strong and having failed to assert a new empire of their own under Jarasan-

Page – 193 dha, they seem to have turned with one consent to Yudhishthira as the man who could alone realise their ideal. One of Shishupal's remarks in the Rajsuya sacrifice is very significant:

We remember that it was an Eastern poet who had sung, perhaps not many centuries before, in mighty stanzas, the idealisation of Imperial Government and Aryan unity and enshrined in his imperishable verse the glories of the third Koshalan Empire. The establishment of Aryan unity was in the eyes of the Eastern nations a holy work and the desire of establishing universal lordship with that view a sufficient ground for putting aside personal feelings and predilections in order to farther it. Shishupala, one of the most self-willed and violent princes of his time, had been one of the most considerable and ardent supporters of Jarasandha in his attempt to establish a Magadhan empire. The divisions of the Central nations follow an equally intelligible line. Throughout the Mahabharata we perceive that the great weakness of the Kurus lay in the division of their counsels. There was a peace party among them led by Bhishma, Drona, Kripa and Vidura, the wise and experienced statesmen who desired justice and reconciliation with Yudhishthira and a war-party of the hot-blooded younger men led by Kama, Duhsasana and Duryodhana himself who were confident of their power of meeting the world in arms; King Dhritarashtra found himself hard put to it to flatter the opinions of the elders while secretly following his own predilections and the ambitions of the younger men. These are facts patent on the face of the epic. But it has not been sufficiently considered what a remarkable fact it is that men of such lofty character as Bhishma and Drona should have acted against their sense of right and justice and fought in what they had repeatedly condemned as an unjust cause. If Bhishma, Drona, Kripa, Ashwatthama and Vikarna had plainly intimated to Duryodhana that they would support Yudhishthira with their

Page – 194 arms or even that they would stand aloof from the war, it is clear there would have been no war at all. And I cannot but think that had it been a question purely between Kuru and Kuru, this is the course they would have adopted. But Bhishma and Drona must have perceived that behind the Pandavas were the Panchalas and Matsyas. They must have suspected that these nations were supporting Yudhishthira not out of purely disinterested motives but with certain definite political objects. Neither Drupada nor Virata would have been accepted by India as emperors in their own right, any more than say Sindhia or Holkar would have been in the last century. But by putting forward the just claims of a prince of the imperial Bharata line, the descendant of Bharata Ajamida, connected with themselves by marriage, they could avoid this difficulty and at the same time break the power of the Kurus and replace them as the dominant partners in the new Empire. The presence of personal interests is evident in their hot eagerness for war and their unwillingness to take any sincere steps towards a just and peaceful solution of the difficulty. Their action stands in striking contrast with the moderate statesmanlike yet firm policy of Krishna. It can hardly be supposed that Bhishma and the Kuru statesmen of his party were autonomists; they must have been as eager for a Kuru empire as Duryodhana himself. At any rate they eagerly welcomed the statesmanlike reasoning of Krishna when he proposed to King Dhritarashtra to unite the forces of Pandava and Kaurava and build up a Kuru empire which should irresistibly dominate the world. "On yourself and myself," says Krishna, "rests today the choice of peace or war and the destiny of the world; do your part in pacifying your sons, I will see to the Pandavas" —

Page – 195

But the empire of Yudhishthira enforced by the arms of Matsya and Panchala or even by the armed threats meant to Bhishma and Kripa something very different from a Kuru empire; it must have seemed to them to imply rather the overthrow and humiliation of the Kurus and a Panchala domination under a Bharata prince. This it concerned their patriotism and their sense of Kshatriya pride and duty to resist so long as there was blood in their veins. The inability to associate justice with their cause was a grief to them, but it could not alter their plain duty. Such as I take it is the clear political story of the Mahabharata.

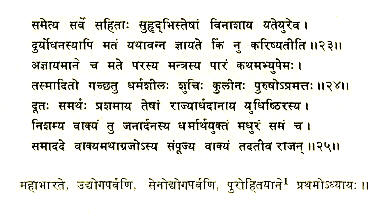

¹Mahabharata, Udyogaparva, 95.16-21, 23-27.

Page – 196 2

THE problem of the Mahabharata, its origin, date and composition, is one that seems likely to elude scholarship to times indefinite if not for ever. It is true that several European scholars have solved all these to their own satisfaction, but their industrious and praiseworthy efforts.... In the following pages I have approached the eternal problem of the Mahabharata from the point of view mainly of style and literary personality, partly of substance; but in dealing with the substance I have deferred questions of philosophy, allusion and verbal evidence to which a certain school attach great importance and ignored altogether the question of minute metrical details on which they base far-reaching conclusions. It is necessary therefore out of respect for these scholars to devote some space to an explanation of my standpoint. I contend that owing to the peculiar manner in which the Mahabharata has been composed, these minutiae of detail and word have very little value. The labour of this minute school has proved beyond dispute one thing and one thing only, that the Mahabharata was not only immensely enlarged, crusted with interpolations and accretions and in parts rewritten and modified, but even its oldest parts were verbally modified in the course of preservation. The extent to which this happened has, I think, been grossly exaggerated, but that it did happen, one cannot but be convinced. Now if this is so, it is obvious that arguments from verbal niceties must be very dangerous. It has been sought to prove from a single word, suranga, an underground tunnel, which European scholars believe to be identical with the Greek suringks that the account in the Adiparva of the Pandavas' escape from the burning house of Purochana through an underground tunnel must be later than another account in the Vanaparva which represents Bhima as carrying his brothers and mother out of the flames; for the former they say must have been composed after the Indians had learned the Greek language and culture and the latter, it is assumed, before that interesting period. Now whether suranga

Page – 197 was derived from the Greek suringks or not, I cannot take upon me to say, but will assume on the authority of better linguists than myself that it was so — though I think it is as well to be sceptical of all such Greek derivations until the connection is proved beyond doubt, for such words even when not accounted for by Sanskrit itself may very easily be borrowed from the original languages. Bengali, for instance, preserves the form "Sudanga" where the cerebral letter is Dravidian. But if so, if this word came into fashion along with Greek culture, and became the word for a tunnel, what could be more natural than that the reciter should substitute for an old and disused word the one which was familiar to his audience? Again much has been made of the frequent occurrence of Yavana, Vahlika, Pehlava, Saka, Huna; as to Yavana its connection with Iaon does not seem to me beyond doubt. It was certainly at one time applied to the Bactrian Greeks, but so it has been and is to the present day applied to the Persians, Afghans and other races to the northwest of India. Nor is the philological connection between Iaon and Yavana very clear to my mind. Another form Yauna seems to represent Iaon fairly well; but are we sure that Yauna and Yavana were originally identical? A mere resemblance however close is the most misleading thing in philology. Upon such resemblances Pocock made out a very strong case for his theory that the Greeks were a Hindu colony. The identity of the Sakas and Sakyas was for a long time a pet theory of European Sanskritists and on this identity was based the theory that Buddha was a Scythian reformer of Hinduism. This identity is now generally given up, yet it is quite as close as that of Yavana and Yauna and as closely in accordance with the laws of the Sanskrit language. If Yauna is the original form, why was it changed to Yavana? It is no more necessary than that mauna be changed to mavana. If Yavana be earlier and Yauna a Prakrit corruption, how are we to account for the short 'a' and the 'v'; there was no digamma in Greek in the time of Alexander. But since the Greeks are always called Yavanas in Buddhist writings, we will waive the demand for strict philological intelligibility and suppose that Yavana answers to Iaon. The question yet remains: when did the Hindus become acquainted with the existence of

Page – 198 the Greeks ? Now here the first consideration is: why did they call the Greeks Ionians and not Hellenes or Macedonians ? That the Persians should know the Greeks by that name is natural enough, for it was with the Ionians that they first came into contact; but it was not Ionians who invaded India under Alexander, it was not an Ionian prince who gave his daughter to Chandragupta, it was not an Ionian conqueror who crossed the Indus and besieged....¹ Did the Macedonians on their victorious march give themselves out as Ionians ? I for my part do not believe it. It is certain therefore that if the Hindus took the word Yavana from Iaon, it must have been through the Persians and not direct from the Greek language. But the connection of the Persians with India was as old as Darius Hystaspes who had certainly reason to know the Greeks. It is therefore impossible to say that the Indians had not heard about the Greeks as long ago as 500 B.C. Even if they had not, the mention of Yavanas and Yavana kings does not carry us very far; for it is evident that in the earlier parts of the Mahabharata they are known only as a strong barbarian power of the North West, there is no sign of their culture being known to the Hindus. It is therefore quite possible that the word Yavana now grown familiar may have been substituted by the later reciters for an older name no longer familiar. It is now known beyond reasonable doubt that the Mahabharata war was fought out in or about 1190 B.C.;² Dhritarashtra, son of Vichitravirya, Krishna, son of Devaki and Janamejaya are mentioned in Vedic works of a very early date. There is therefore no reason to doubt that an actual historical event is recorded with whatever admixture of fiction in the Mahabharata. It is also evident that the Mahabharata, not any "Bharata" or "Bharati Katha" but the Mahabharata existed before the age of Panini, and though the radical school bring down Panini the next few centuries... (Incomplete) ¹Word missing. ²This date was accepted by Sri Aurobindo at the time of writing. On p. 66 of his Gitar Bhumika (in Bengali—written in 1909) he says: "It should be remembered that the war of Kurukshetra took place 5000 years ago." It may be that later he accepted still another date.

Page – 199 The Problem of the Mahabharata NOTES

Notes on the Mahabharata dealing with the authenticity of each separate canto i.e. whether it belongs or not to the original epic of 24,000 Slokas on the great catastrophe of the Bharatas.

UDYOGAPARVA CANTO ONE

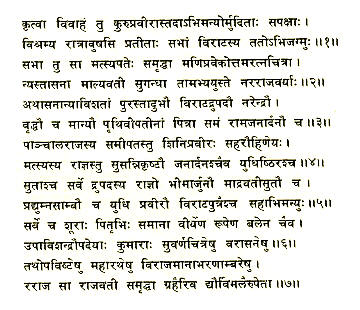

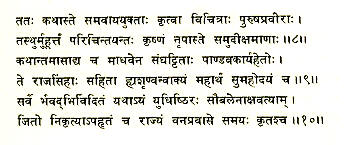

1. Kurupravīrāh...sapaksāh — This may mean in Vyasa's elliptic manner the Great Kurus (i.e. the Pandavas) and those of their side. Otherwise "The Kuru heroes of his own side", i.e. Abhimanyu's, which is awkward.

3. Vrddhau — This supplies the reason of their pre-eminence.

5. Pradyumna-sāmbau ca yudhi pravīrau. This establishes Pradyumna and Samba as historical sons of Krishna. Virātaputraiśca — Virata has therefore several sons, three at least.

Page – 200 7. The simile is strictly in the style of Vyasa who cares little for newness or ingenuity, so long as the image called up effects the purpose. The assonance rarāja sā rājavatī is an epic assonance altogether uncommon in Vyasa and due evidently to the influence of Valmiki.

8. Strong, brief and illumining strokes of description which add to the naturalness of the scene, tatah kathāste samavāyayuktāh: while also adding a touch that reveals the inwardness of the situation:

krtvā vicitrāh purusa-pravīrāh,

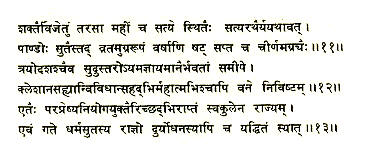

9. Samghattitāh — surely means "assembled" and nothing else. P. C. Roy in taking it as "drew their attention to" shows his usual slovenliness. Lele also errs in his translation. He interprets it: "as soon as the talk was over Krishna assembled the kings for the affairs of the Pandavas." But the kings were already assembled and seated; not only so but they were waiting for Krishna to begin. It is absurd to suppose that as soon as Krishna began speaking they left their seats and clustered around him like a pack of schoolboys. Yet this is the only sense in which we can take Lele's rendering. I prefer to take the obvious sense of the words: "As soon as they had reached an end of talk, all those lion-kings assembled by the den of Madhou in the interests of the Pandava listened in a body to his high-thoughted and fateful speech." Sumahodayam — having mighty consequences.

10. Ayam — here beside me. See verse 4. Yudhishthira is sitting just by Krishna separated by Virata.

Page – 201 11. Tarasā — taras expresses any swift, violent and impetuous act, anything that has the momentum of strength and impulse or fire and energy. Satyarathaih — This is a word of doubtful import; it may mean "of unerring chariots", i.e. skilful fighters, or else "honourable fighters", rathah being used as in mahārathah, adhirathah fighter in a chariot. Cf. satyaparākramah. In the first case the epithet would be otiose and ornamental and an epic assonance. I cannot think however that Vyasa was capable of putting a purely decorative epic epithet in so emphatic a place. It must surely mean either "honourable fighters" or "making truth their chariot"; ratha being used as in manoratha etc. The latter however is almost too much a flight of fancy for Vyasa. [The word is satye sthitaih, according to another version.]

12. Trayodaśaścaiva, — agreeing with Samvatsara which the mind supplies from varsāni in the last line and Virvatsa has to be supplied from Chirnam. This is the true Vyasa style. Nivista — niviś : to abide. This sense though not given in Apte may be deduced from niveśah : impersonal "it has been dwelt".

13. It will be seen from Krishna's attitude here as elsewhere that he was very far from being the engineer and subtle contriver of war into which later ideas have deformed him. That he came down to force on war and destroy the Kshatriya caste, whether to open India to the world or for other cause, is an idea that was not present to the mind of Vyasa. Later generations writing, when the pure Kshatriya caste had almost disappeared, attributed this motive for God's descent upon earth, just

Page – 202 as a modern English Theosophist, perceiving British rule established in India, has added the corollary that he destroyed the Kshatriyas (five thousand years ago, according to her own belief) in order to make the line clear for the English. What Vyasa, on the other hand, makes us feel is that Krishna, though fixed to support justice at every cost, was earnestly desirous to support it by peaceful means if possible. His speech is an evident attempt to restrain the eagerness of the Matsyas and Panchalas who were bent on war as the only means of overthrowing the Kuru domination.

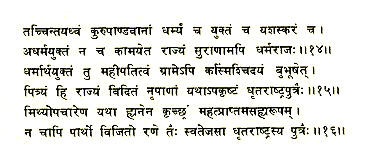

14-15. Krishna's testimony to Yudhishthira's character is here of great importance.

Adharmayuktam na ca kāmayeta rājyam surānāmapi dharmarājah. That Yudhishthira has deserved this character to the letter so far anyone who has followed the story will admit. If he acts in diametrical opposition to this character in any future passage we shall have some ground to pause before we admit the genuineness of the passage. Bubhūset — desiderative of bhū in the sense of "get, obtain", "would aspire after".

16. Mithyopacārena — by fraudulent procedure. That is, if Duryodhana had taken the kingdom from the Pandavas in fair war by his own energy and genius (svatejasā), he would not have transgressed the ordinary Dharma of the Kshatriya. In that case the Pandavas might have accepted the verdict of Fate and refrained from plunging the country in farther bloodshed.

Page – 203 17. Prapīdya [nipidya — another version] by force, pressure; as a result of conquest in open battle. This seems to point to the Vijayaparva; but the reference is general and may apply to the Rajasuya generally. Tu — The force is "but you know what the Dhartarashtras are, their fierceness, falseness and land-hunger, — how even in the childhood of the Pandavas these, their banded foemen, sought to slay them by various means". For he evidently desired to try conciliation first, before resorting to threats. The choice of the Purohita was that of King Drupada, and the leaders of the Brahmavarta nations who desired to break the supremacy among them of the Kurus.

18. Bālāstvime — An allusion to the early persecution of the Pandavas by Duryodhana. If we accept this Parva in its completeness, we must accept the genuineness in the main of the early narrative of the Adiparva in so far as it is covered by the Sloka. Notice especially vividhairupāyaih.

19. This seems to point to the Digvijaya Parva; but the reference is general and may apply to the Rajasuya generally.

22. Tathāpi — for all their good will. It is part of the inverted commas implied in iti.

Page – 204 23. Yateyureva — would at least do their utmost. Yathāvat — definitely; though they may form a shrewd guess.

25. Rājyārdhadānāya — Krishna does not, at present at any rate, suggest a compromise; let them first make their full claim to which they are entitled (notice genitive). This canto is in the very finest and most characteristic style of Vyasa; precise, simple and hardy in phrasing, with a strong, curt, decisive movement and a pregnant mode of expression, in which a kernel of thought is expressed and its corollaries suggested so as to form a thought-atmosphere around it. There is no superfluous or lost word or sentence, but each goes straight to its mark and says something which wanted to be said. The speech of Krishna is admirably characteristic of the man as we have seen him in the Sabhaparva; firm and precise in outlook and sure of its own drift, it is yet full of an admirable and disinterested statesmanlike broadmindedness.

¹Purohitāyane — This title is evidently a misnomer; there is no mention of the Purohita, far less does he set out as yet nor need we suppose he is hinted at in the description of a suitable envoy. It is doubtful whether Krishna would have singled out a Panchala Purohita as the best intermediary between the Kurus for he evidently desired to try conciliation first, before resorting to threats. The choice of the Purohita was that of King Drupada and the leaders of the Brahmavarta nations who desired to break the supremacy among them of the Kurus.

Page – 205 CANTO TWO

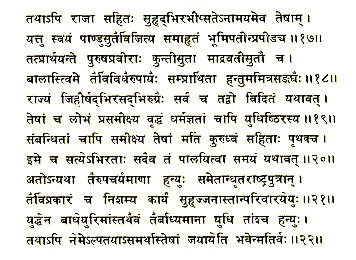

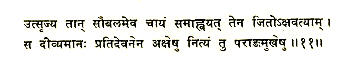

Divyamānah pratidevanena — Can this not mean "being challenged to dice placed against Saubala or in acceptance of the challenge", or must it mean "gambled and that against Saubala" ?

Page – 206 Udyogaparva*

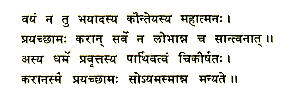

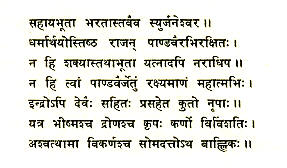

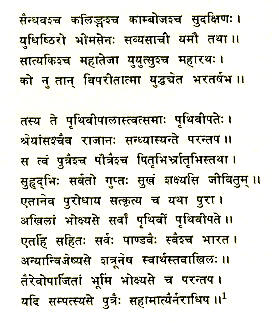

LET the reciter bow down to Naraian, likewise to Nara the Highest Male, also to our Lady the Muse (Goddess Saraswati), and thereafter utter the word of Hail! Vaishampayan continueth But the hero Kurus and who clove to them thereafter having performed joyously the marriage of Abhimanyu rested that night and then at dawn went glad to the Assembly-hall of Virata. Now wealthy was that hall of the lord of Matsya with mosaic of gems excellent and perfect jewels, with seats set out, garlanded, perfumed; thither went those great among the kings of men. Then took their seats in front the two high kings, Drupada and Virata, old they and honoured of earth's lords, and Rama and Janardan with their father. Now by the Panchala king was the hero Shini with the son of Rohinie but very near likewise to the Matsya king Janardan and Yudhishthira; And all the sons of Drupada, Bhima, Arjuna and the sons of Madravatie and Pradyumna and Samba, heroes in the strife, and Abhimanyu with the children of Virata; And all those heroes equal to their fathers in heroism and beauty and strength sat down, the princely boys, sons of Draupadie, on noble seats curious with gold. Thus as those great warriors sat with shining ornaments and shining robes, rich shone that senate of kings like wide heaven with its stainless stars.

*

"To all of you it is known how Yudhishthira here was conquered by Saubala in the hall of the dicing; by fraud was he conquered and his kingdom torn from him and contract made of

* Translation of Adhyaya 1.1-7, 10-26.

Page – 207 exile in the forest; and though infallible in the mellay, though able by force impetuous to conquer the whole earth, yet the sons of Pandu stood by their honour religiously; harsh and austere their vow but for the six years and the seven they kept it, noblest of men, the sons of Pandu; and this the thirteenth year and most difficult they have passed before all your eyes unrecognised; in exile they passed it, the mighty-minded ones, suffering many and intolerable hardships, in the service of strangers, in menial employments cherishing their desire of the kingdom that belongeth to their lineage. Since this is so, do ye think out somewhat that shall be for the good both of the King, the son of Righteousness and of Duryodhana, just and glorious and worthy of the great Kurus; for Yudhishthira the just would not desire even the kingship of the gods unjustly, yet would he cling to the lordship of some small village which he might hold with expediency and justice. For it is known to you kings that how by dishonest proceeding his father's kingdom was torn from him by the sons of Dhritarashtra and himself cast into great and unbearable danger; for not in battle did they conquer him by their own prowess, these sons of Dhritarashtra; even so the king with his friends desired the welfare of his wrongers. But what the sons of Pandu with their own hands amassed by conquest crushing the lords of earth, that these mighty ones demand, even Kunti's sons and Madravatie's. But even when they were children, they were sought by various means to be slain of their banded foemen, savage and unrighteous, for greed of their kingdom, yea all this is known to you utterly. Considering therefore their growing greed and the righteousness of Yudhishthira, considering also their close kinship, form you a judgment each man to himself and together. And since these have always clung to truth and loyally observed the contract, if they know they are wronged, they may well slay all the sons of Dhritarashtra. And hearing of any wrong done by these in this business their friends would gather round, the Pandavas, yea and repel war with war and slay them. If natheless ye deem these too weak in numbers for victory, yet would they all band together and with their friends at last to strive to destroy them. Moreover none knoweth the mind of Duryodhana rightly, what he meaneth to do, and

Page – 208 what can you decide that shall be the best to set about when you know not the mind of your foeman ? Therefore let one go hence, some virtuous, pure-minded and careful man such as shall be an able envoy for their appeasement and the gift of half the kingdom to Yudhishthira. This hearing, the just, expedient, sweet and impartial speech of Janardan, the elder brother of him took up the word, O prince, honouring the younger's speech even greatly." (Incomplete)

Page – 209 |